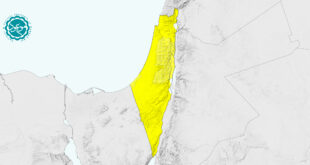

How Israel’s Fear of Arab Democracy Leaves the Jewish State More Isolated

By Alex Kane

Middle East expert Reem Abou-El-Fadl explains how Arab solidarity with the Palestinians is being reflected at the official level in the aftermath of the Arab Spring.

Egyptians demonstrate outside the Israeli embassy .

Photo Credit: Gigi Ibrahim/FlickrAs the struggle for democracy and dignity in the Arab world rages on in countries like Tunisia and Egypt, the Israeli establishment’s response has been to disparage the revolts and hunker down.Israel’s right-wing leader, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, laid out this response in a speech to the Israeli Knesset last year. The Arab revolts have turned into an “Islamic, anti-Western, anti-liberal, anti-Israeli and anti-democratic wave,” Netanyahu said. “Israel is facing a period of instability and uncertainty in the region.”The implication was that this is no time for a peace agreement with the Palestinians or Israel’s Arab neighbors.

Netanyahu’s right about the Israeli regional position. Outrage in the Middle East at Israeli violations of Palestinian human rights –which had bubbled below the surface in Western-backed dictatorships–has been unleashed. There’s a long history of popular solidarity with the Palestinians suffering under Israeli rule in the Arab world, and the popular uprisings have begun to transfer that solidarity onto the official level, as Dr. Reem Abou-El-Fadl explained in an interview with AlterNet.

An expert on Egypt and Turkey who witnessed the protests in Egypt last year, Abou-El-Fadl is a fellow at Oxford University. She recently authored a piece in the Journal of Palestine Studies arguing that anti-Zionism and Palestine solidarity was an important but overlooked element of the Egyptian uprising that brought down Hosni Mubarak.

I caught up with Abou-El-Fadl over Skype for an in-depth look at Israel’s regional position in the Arab world.

Alex Kane: First, summarize the regional position Israel has been in since the founding of the state in 1948. How would you describe Israeli relations with its neighbors?

Reem Abou-El-Fadl: Israel has always been deeply unpopular in the Arab world. It was born through ethnic cleansing and expulsion in 1948, and it was seen after that as an extension of Western colonialism. So Israel’s relations with its neighbors generally were hostile. Palestinians and other Arabs on the popular level saw that the first Zionist settlers were supported by the British, who were ruling Palestine under the Mandate system at the time, who were also exerting colonial control over other Arab lands. And in fact, it was popular pressure that forced the client governments in Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Jordan to send troops in May 1948 to try to overcome the nascent Israeli forces, and we know that they failed.

After that, I’d say there are a couple of different phases. In the 1950s and ’60s, you had decolonization in states like Egypt. The Arab world saw a division between two main camps: you had the pan-Arabist, anti-colonial camp, in which Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt played a main role, and he championed Palestinian rights, and the other camp was the conservative monarchies. They were allied with the British and later the US, and their regional role was to undermine the Nasserist camp, and therefore indirectly ease the pressure on Israel.And then in 1967 there was an important watershed. Israeli expansionism and war defeated Egypt and Syria and gained more Arab territory–the West Bank, Gaza, South Lebanon, the Golan area, Sinai in Egypt. And the pan-Arabist camp was very much weakened. So the tide then switched to still-hostile relations with Israel, but mediated through pan-Arab support for direct Palestinian resistance.

And then you have President Anwar El Sadat in Egypt opening the door to normalization and peace with Israel. He signs the peace treaty in 1979, which paves the way for the Oslo Accords and the Israeli-Jordanian peace in the 1990s. So that brings us into the phase where you have a cold peace between Egypt and Israel and a failing peace process with the Palestinians, while the conservative states remained where they were, empowered by their US alliance. Generally, the Arab populations never accepted Israel, but its military might and international support helped it engineer a weak set of neighbors.

AK:And would you say that the Arab uprisings have begun to change the status quo situation for Israel?

RF: First, let’s quickly recap what we think the status quo was. In the past 10 to 20 years, you had Western-backed dictatorships, which had become very pliant regarding Israel–I mean, signing a peace treaty is one thing, but Mubarak’s relations with Israel reached what many people called partnership levels. So he was facilitating Israel’s freedom of maneuver in its oppression in occupied Palestine, in its siege of Gaza, and so on.

When Ben Ali in Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt were knocked out with such force, Israel lost two major allies, and it became clear that the new leaderships would have to be more representative, and that the Arab popular will is resoundingly anti-Zionist and pro-Palestinian. This implied for Israel that its isolation would spread from the popular masses to the leaderships governing them. So that put Israel on the defensive since early 2011. Tunisian and Egyptian protesters, when they talked about human dignity and talked about patriotic policies, this is very much a reference to foreign policy.

We haven’t seen major policy changes on the part of the Arab leaderships — we’re still very much in transition in some of these cases — but it’s also safe to say that they’ll be no return to the free rein Israel had in the past 20 years. And leaderships now, even if they haven’t been democratized or revolutionized, are on the defensive with their people in regards to policy on Israel. I think the fact that the US is having to reassess its position in the region, reassess the way in which it presents its rhetorical support for democracy in the region, these are all signs that the Arab uprisings have changed Israel’s environment, even if we can’t point to many concrete policy changes, though the recent cancellation by Egypt of the gas deal with Israel is an important exception.

AK: I want to hone in on Egypt. Your article in the Journal of Palestine Studies cuts against the grain of what was the conventional wisdom in the United States when the uprisings first broke out. There was a lot of talk about how these protests are not focused on the US and Israel, they’re about their own countries, and what a break this is. Talk about why that’s wrong.

RF: My interest in writing on this topic came out of frustration with the mainstream coverage of the Egyptian revolution — and of course in Israeli coverage, which embodied this trend — this idea that it was a myth that Arab people cared about Palestine, that it was just something leaders used to distract us with. For some of the pundits in the West, precisely because these dictators had been so staunchly backed by the West, it was convenient to focus on the domestic demands of the protesters and move away from this idea of any culpability for the West in propping up these regimes. So I wrote this article to show that domestic and foreign policy concerns are intertwined in protesters’ conceptions, and that this has been the case for four decades of popular protest in Egypt.

While the most obvious demand during the 2011 uprising was domestic in the sense that it was Mubarak’s downfall people were after, the demands raised in the first 18 days made frequent reference to Mubarak’s unpopular foreign policy, and here Israel was a state frequently mentioned. It wasn’t so much about Palestine, but about what people called Egypt’s “shameful” relations with Israel, embodied in the Egyptian-Israel gas deal and Camp David itself. After Mubarak was toppled, the revolutionary forces initially believed they were represented in government. There wasn’t this sense that’s very clear right now across the board that the military council wasn’t going to uphold the revolution’s demands. So in those honeymoon months, demands for foreign policy were pushed to the fore. And within a couple of weeks of Mubarak’s departure, you had protests move from Tahrir Square to the Israeli Embassy. And this was then building up to the massive Nakba demonstrations in May last year that filled Tahrir Square. People had this idea that once domestic change was assured, we move onto our foreign policy demands.

The second half of 2011 sees a litany of attacks on protesters, which were coordinated with or orchestrated by the military council. Then you see the protesters revert back to this tactical pushing of domestic demands and demotion of foreign policy demands.

Some proof that this was only tactical came with the August 2011 flare-up. There were six Egyptian soldiers killed on the border by Israeli forces and this came at a time when the mobilization in Tahrir Square was focused on the military council. Suddenly, these six soldiers are killed, and the mobilization shifts back to the Israeli embassy, and peaks with the bringing down of the Israeli flag. After that, you see less overt mention of foreign policy, but this is because revolutionary forces have been placed on the defensive and forced to justify even their existence. But it does not mean foreign policy has not been consistently embraced as a demand by these forces. Further evidence is the visible effort made by all presidential candidates, across the board, to sound decisive and hostile vis-a-vis Israel in their campaigns.

AK:Do you think that the presidential elections in Egypt will affect the country’s relations with Israel?

RF: The first thing to say is that these presidential elections, their timing and their rules and the very candidates who are running, were imposed by the military council. For example, Mubarak-era figures are not excluded, a constitution is not yet written, and those responsible for the killing of protesters last year have not been brought to justice first. So the legitimacy of the new president is definitely questionable, and there’s already a large number of citizens boycotting these elections.

On the other hand, the elections are widely seen as the main fruit of the revolution, and a democratic breakthrough. Many people are voting, and that’s mainly because even if they don’t trust the generals, they want to thwart their plans. But I doubt the new candidate will be in a wrangle with the ruling generals because if we just look at the political scene, the elections come at a very uncertain time for the Egyptian forces for change. They’ve been systematically attacked, both physically and in the media, in the last year. So you have today a situation of division among those groups that claim to represent the millions who ousted Mubarak, and those millions would be looking for a change in policy on Israel.

The candidate who comes through these far from free elections will likely not be at odds with the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces’ policy with Israel. But, that’s going to be tempered because of the popular will and how its inserted itself into high politics. The revolution did happen, as much as these military generals are trying to derail it and act like it didn’t happen. It’s a question then of these leaders being sensitive to the levels to which they can push on policies with Israel and the privileges they get from the US as a result.

AK:I have one more question. Tensions with Israel and Turkey have increased in the past year, although these tensions are separate from the Arab revolts. Could you talk about Israeli-Turkish relations and what that means for Israel’s position in the region?

RF: As you said, the Arab world is going through uprisings, and movements for political change, and they have implications for Israel that are popularly driven. The case of Turkey is different because the recent tensions with Israel have come from official policy, and even in some readings it’s directly connected to manipulation of popular opinion, or an attempt to distract people away from domestic problems. Turkey has been accused of becoming increasingly draconian with dissent from Kurdish and leftist quarters.

The context of this is there was a period during the second AKP [the ruling party] term when its government did move towards a critique of Israeli policy. What we saw was a pragmatic shift by Turkey after it was snubbed by the European Union, to take advantage of its location and ties with its neighbors and to make serious economic gains in fostering trade and soft power in the Arab world. And the grandstanding on Israel at this time was largely verbal.

The tipping point came when the Israeli government snubbed the AKP government amidst Turkey’s mediation role between Syria and Israel and launched its war on Gaza without so much as a warning to Turkey, which angered the Turkish leadership profoundly. And it was followed by a series of different hostile incidents, one of them being the dressing down of the Turkish ambassador in public in Tel Aviv and the other was the killing of nine Turks aboard the Mavi Marmara. If you think about the Turkish government, elected by half the population, the freezing of relations with Israel was a necessary response before its people. Anything less than that was not a policy option, and we have to remember the freezing of relations occurred last year, a full year after the Mavi Marmara. But if we look at the big picture, trade relations between Turkey and Israel have continued, and military maneuvers have been conducted together that last year had largely slowed down.

And if we also look at Turkey’s role in Syria recently, this in a way brings us back to before its coldness with Israel. Turkey is supporting the Syrian National Council, which is one branch of the Syrian opposition, that has a conciliatory line on Israel. So Turkey’s positioning itself as being in the forefront of regional actors in the US camp, and is working alongside conservative Gulf powers like Qatar and this constellation of forces does not seek to destabilize the relationship with Israel. So we need to keep that in mind.I should say that Israel today does have to work harder in diplomacy in the public spheres to hide its crimes. But this is because pressure from below, like the thousands of Palestinian prisoners who went on hunger strike recently, because of the refugees who before the world’s eyes crossed barbed wire on Nakba Day last year to see their homes, and because of the intensity of resentment expressed towards Israel during popular uprisings like Egypt’s. This is what has exposed Israel’s isolation and this is what continues to disturb the Israeli establishment.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition