Our experience of ourselves as separate and isolated from other people means that we have particularly hostile and fearful relationships with others, and these feelings are exaggerated when we relate to those in authority. The beliefs that we have deep down about our own nature and about those lesser and greater than ourselves are forms of ideology.

sense of emptiness that consumerism promises, but intrinsically Late capitalist societies operate upon the mechanisms of social isolation. They create a social vacuum and an individualized fails, to satisfy. In such a situation, salvation through the spirituality market covertly provides new resources for sustaining the materialistic culture that they are ostensibly seeking to resist.

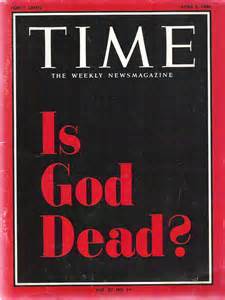

The introduction of ‘private’ models of spirituality can be a dangerous move, especially in the helping professions and pastoral care. In the very desire to cure the addictions of modern living, patients are offered models of ‘spirituality’ to provide greater meaning in an empty world. This capitalist spirituality, however, only increases private consumer addiction. It offers personalised packages of meaning and social accommodation rather than recipes for social change and identification with others. In this sense, capitalist spirituality is the psychological sedative for a culture that is in the process of rejecting the values of community and social justice. The cultural hegemony of this kind of spirituality grows as market forces increase and as neoliberal ideology is unhindered in its takeover of all aspects of human life and meaning. The desire for more diverse forms of spirituality to counter the ideology of consumption increases with the everperpetuating production line of new ‘spiritual’ products. The vacuous nature of the ‘spiritual’ marketplace creates a greater demand and need for some kind of ‘real’, ‘pure’ or ‘authentic’ spiritual experience, always just out of reach, like the inner contentment that consumerism promises but never fulfils. The consumer world of ‘New Age’ spirituality markets ‘real’, ‘pure’ or ‘authentic’ spiritual experiences, but these are manufactured worlds that seek to escape the ‘impure’ political reality of spirituality. The problem is always to identify which ideology is constructing and informing the idea of spirituality at any particular point in history. Capitalist spirituality only raises the desire for ever-new versions of spirituality that reinforce our private and isolated worlds. In the end, such spiritualities are too easily co-opted by the desiring machine of consumerism. Writing in 1970, Erich Fromm (1995: 67) had already appreciated that

Man [sic] is in the process of becoming a homo consumens, a total

consumer. This image of man almost has the character of a new religious vision in which heaven is just a big warehouse where everyone

can buy something new every day, indeed, where he [sic] can buy everything that he wants and even a little more than his neighbour. This vision of the total consumer is indeed a new image of man that is conquering the world, quite regardless of the differences of political organisation and ideology.

What we are calling, respectively, individualist/consumerist and corporatist/capitalist spiritualities devalue embodied communities by increasing the self-importance of individuality (or the corporation) and placing the pursuit of individual (and/or corporate) wealth above social justice. These forms of spirituality are the result of a failure to recognise that individuality is born out of community and that ‘spirituality’, as a psychological reality, is a hidden form of social manipulation of the same order as oppressive forms of thoughtcontrol associated with religious traditions in previous eras. More importantly, what such forms of spirituality leave behind in their distillation of the spiritual from the religious are the resources of social conscience and community identity that those traditions provided for humanity.

Socially engaged forms of spirituality do not eradicate a concern for the individual, but rather reject the idea that the individual is a separate entity to be measured for the purposes of social control and consumption. As some forms of ‘critical psychology’ have emphasised, the individual is always social. The individual sense of self reflects and shapes the social world, either in the negative form of isolation or in a positive form as social integration. Socially engaged forms of spirituality recognise that the sense of self must be built on social networks, not on private separation and individual consumption. As Stanczak and Miller (2002: 24) have identified in a recent report on Engaged Spirituality: ‘spirituality only becomes enacted for social transformation when the spiritual experiences find personal resonance with motivations and available patterns ofTM action for bringing about social change’. Such engaged approaches locate spirituality and individual identity within the social fabric, and

possession. When the individual self is seen as a node in a web of recognise that our sense of personal worth is grounded upon social value and relationship, not upon private gratification and individual social relations, one can see the need for pastoral care, ‘New Age’ healing and the helping professions to become politically informed activities that seek personal health through social justice and social amelioration. Individual mental health can only be established through socially embedded structures that seek justice for all and not gain for the few, because individuals depend upon each other and evolve together and not in isolation. Individual dis-ease is always in part a dis-ease of society (especially when it comes down to the allocation of social resources). In this respect, a ‘spirituality’ that is separate from questions of social justice is a sedative for coping with an oppressive and difficult world.

In 1932 at the Alsatian Pastoral Conference at Strasbourg, Jung (1958: 334) recognised that his patients were suffering from a lack of religious perspective. It now seems that individual suffering, loneliness and isolation are themselves consequences of a ‘capitalist’ spirituality that has lost its social ethic. The full consequences of this production of spirituality are as yet unknown, but what becomes clear is that psychological spirituality hides its political allegiance to a consumer world. As long as spirituality operates according to the dictates of global capitalism it will continue to contribute to the breaking up of traditional communities and the undermining of older, indigenous forms of life around the world. Capitalist spirituality, however, can be overcome by consideration of the forgotten social dimensions of ‘the religions’, by rescuing and developing alternative models of social justice, and by contesting the corporatisation and privatisation exemplified in such contemporary forms of spirituality.

In conclusion, we have seen how the history of psychology is bound up with capitalism through the privatisation of human experience. When psychology ideologically reshapes religion, it creates the possibility of a spirituality for the marketplace. In this context, it is vital, as Helen Lee (2001: 155) has argued, that ‘contemporary notions of spirituality, however conceived, are not romanticised as ideal and accepted unquestionably as the way forward in the twenty-

the process of privatising religious experience has also been carried first century’. While much of the discussion in this chapter has focused upon the transformations of the inner world of western Christianity,

forward in relation to other traditions. Indeed, as we shall see in the next chapter, the very assimilation of Asian traditions and culture into the marketplace of religions has occurred precisely through this reorganisation of experience in the terms set by psychology.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition