In 1950, the Harvard psychologist Gordon Allport advanced the privatisation of religion in his work The Individual and His Religion. In attempting to develop a positive religious sentiment, Allport upheld the American values of democracy and freedom of choice to create an engagement with religion that allowed a rejection of tradition and the cultivation of individual personality as a new religious space. Developing the work of Friedrich Schleiermacher, William James and Rudolf Otto, Allport rejected institutional religion in order to develop a subjective religious attitude.

The key part of Allport’s project was a gradual erosion of the traditional institutions of (‘immature’) religion to be replaced by a private (‘mature’ and ‘healthy’) religion. Psychology provided the ‘scientific’ legitimation for translating the religious world into a concern for individual health and maturity. This shift away from institutional religion was not just a method of approach as it was for James, it was now fast becoming a question of pathology. The privatisation of religion was the shift in power from the Church to the state apparatus of psychology. The force of religion was taken away from the religious institutions and given over to market forces. Allport was another point along the road to a privateTM spirituality, which would flourish in a consumerist climate. Allport gives priority to ‘individual’ meaning, as he states:

to my mind every supporter of democracy must hold: the right of each

One underlying value judgement flavours my writing. It is a value that

individual to work out his own philosophy of life to find his personal niche in creation, as best he can. His freedom to do so will be greater if he sees clearly the forces of culture and conformity that invite him to be content with a merely second-hand and therefore for him, with an immature religion. It is equally essential to his freedom of choice that he understand the pressures of scorn and intimidation that tend to discourage his religious quest altogether.

(Allport, 1962: vii–viii)

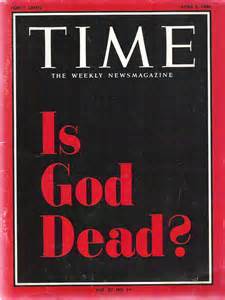

The greatest shift towards private spirituality, however, can be seen in the work of Abraham Maslow, particularly as his work was picked up by the 1960s Hippie culture and dovetailed with the psychedelic world of Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary. In this atmosphere, ‘spirituality’ became a product, like a drug, to change consciousness and lifestyle and provide happiness amidst the economic boom of North American life. Maslow’s work did more for ‘New Age’ spirituality products and their capitalisation than most psychological theories, principally because he created a new terminology for ‘religious experience’, which effectively divorced it from ‘religious tradition’. His ideas of ‘self-actualisation’, ‘peak-experience’, ‘Beingcognition’ and ‘transpersonal psychology’ have all played a key part in the creation of capitalist spiritualities. His language facilitated a clear break of ‘spirituality’ from its institutional moorings, and opened the space for spirituality to be seen as a ‘secular’ rather than an especially ‘religious’ phenomenon.

Maslow reinforced the private, intense model of religious expression that James had constructed half a century earlier. Conducting his analysis of experience according to his already developed model of ‘spiritual’ experience and sampling disillusioned college graduates, Maslow would ask his interviewees about their ecstatic and rapturous moments in life, not realising that religious insight often came fromTM experiences of suffering and denial. This feel-good spirituality of the self was part of the wider process of turning the social ideals of exploration can be seen in the framing of his questions:

religion into the interiorised world of the self, what we have called the ‘psychologisation of religion’. The predetermined nature of Maslow’s

I would like you to think of the most wonderful experience or experiences of your life; happiest moments, ecstatic moments, moments of rapture, perhaps from being in love, or from listening to music or suddenly ‘being-hit’ by a book or a painting, or from some great creative moment. First list these. And then try to tell me how you feel in such acute moments, how you feel differently from the way you feel at other times, how you are at the moment a different person in some ways.

(Maslow, 1976: 67, our emphasis)

Maslow’s psychology was built on the principle of positive motivation towards a healthy realisation of human potential. Like inflation and deflation of the markets, people could reach ‘growth’ motivation in the realisation of love and self-esteem, but much of this echoed the privileges of a wealthy culture, and his famous ‘hierarchy of needs’ was more a hierarchy of ‘capitalist wants’. It reflected a culture where basic physiological needs were excessively fulfilled and even of secondary concern, allowing for the ‘higher’ expressions of cognition, aestheticism and self-realisation. This partition of expression clearly ignored the rich traditions of other cultures where poverty and denial brought about transformation. This was a spiritual message for a culture of excess and one that rejected the shared expression of communal religious faith. It was the birth of a private religion based on individual ‘peak-experiences’. Thus, according to Maslow (1976: 27–8):

the evidence from the peak-experience permits us to talk about the essential, the intrinsic, the basic, the most fundamental religious or transcendent experience as a totally private and personal one which can hardly be shared (except with other ‘peakers’). As a consequence, all the paraphernalia of organised religion – buildings and specialised personnel, rituals, dogmas, ceremonials, and the like – are to theTM ‘peaker’ secondary, peripheral, and of doubtful value in relation to the intrinsic and essential religious or transcendent experience. Perhaps

they may even be very harmful in various ways. From the point of view of the peak-experiencer, each person has his own private religion,

which he develops out of his own private revelations in which are

revealed to him his own private myths and symbols, rituals and

ceremonials, which may be of the profoundest meaning to him

personally and yet completely idiosyncratic, i.e. of no meaning to anyone else. But to say it even more simply, each ‘peaker’ discovers, develops, and retains his own religion.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition