“To this day I have never troubled about the ethics of the matter,” Moreau confides. “The study of Nature makes a man at last as remorseless as Nature. I have gone on, not heeding anything but the question I was pursuing; and the material has — dripped into the huts yonder.”

So traumatized is Prendick by Moreau’s island that when he finally escapes, he is no longer able to tolerate the company of humans, whom he can no longer distinguish from the beasts.

“I look about me at my fellow-men; and I go in fear,” he confesses. “I see faces, keen and bright; others dull or dangerous; others, unsteady, insincere, — none that have the calm authority of a reasonable soul. I feel as though the animal was surging up through them; that presently the degradation of the Islanders will be played over again on a larger scale.”

Which Is Worse?

We are all familiar with a contemporary science fiction character who also suffers from Prendick’s condition. Her name is Ripley, the heroine of the four-part Alien series and played by Sigourney Weaver. In part one of this quartet of intergalactic slasher movies, Ripley works on a commercial freighter spaceship overtaken by extraterrestrial parasites that lethally implant eggs into her shipmates, one by one. To her further horror, she discovers that the android assigned to the flight has been instructed by her corporate employers to preserve the creatures for further study, rather than let her destroy the vessel.

Having escaped and eliminated the freighter anyway, in Aliens Ripley is at first condemned by her employers, who don’t believe her story. But soon they discover that the creatures really exist and have taken over the small planet where her crew first encountered them. Begged to accompany a rescue mission, Ripley only goes along on the proviso that the point is to destroy the monsters, not bring them back to monetize their abilities.

Company agent Carter Burke (played by Paul Reiser), assures her that this is so. But he has lied to her, of course, and tries to trap some of her crew in a laboratory room with one of the creatures in the hope of bringing an impregnated human back to earth and winning a commission.

“You know, Burke, I don’t know which species is worse,” Weaver says to Reiser. “You don’t see them screwing each other over for a fucking percentage.”

By episode four — Alien Resurrection — the military has gotten hold of the beasts and is conducting space station experiments on them with humans. The research gets out of control, and the aliens go wild and take over. Meanwhile Ripley has become part alien herself — cloned after dying, then one of the creatures surgically removed from her chest. She, one of the scientists, and a pirate crew that kidnapped more cryogenically frozen victims for the experiments find themselves fighting for their lives.

When one of the frozen captives wakes up, he demands an explanation. “What’s in-fucking-side me?” he demands.

“There’s a monster in your chest,” Ripley wearily explains. “These guys hijacked your ship, and they sold your cryo tube to this … human. And he put an alien inside of you. It’s a really nasty one. And in a few hours you’re gonna die. Any questions?”

“Who are you?”

“I’m the monster’s mother.”

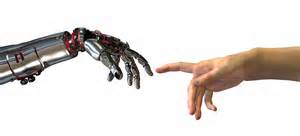

And when Ripley discovers that Annalee Call, one of the pirate crew members, is actually an android (played by Winona Ryder) trying to kill her to destroy the aliens, she is barely surprised. “You’re a robot?” Weaver exclaims. “I should have known. No human being is that humane.”

The episode concludes as Weaver and Ryder descend to Earth in an escape vessel. “What happens now?” Call asks. “I don’t know,” Ripley confesses. “I’m a stranger here myself.”

Like H.G. Wells’ Prendick, Ripley has escaped from the Island of Doctor Moreau. The scale of the experiment is much larger and far more sadistic, but the result is the same. She has lost any ability to see humanness in humans.

The World Set Free

A dozen years after H.G. Wells wrote his most popular works, he gave freer voice to his idealistic visions. These included The World Set Free, a 1914 account of how civilization repaired itself following an atomic war. The human race adopted a single government, Wells explained. It embraced a single language, a single currency and universal education.

“The catastrophe of the atomic bombs which shook men out of cities and businesses and economic relations shook them also out of their old established habits of thought, and out of the lightly held beliefs and prejudices that came down to them from the past,” Wells argued. “To borrow a word from the old-fashioned chemists, men were made nascent; they were released from old ties; for good or evil they were ready for new associations.”

But instead of following these recommendations, the world descended into its first global conflict. Seven years later, Wells admitted that he wasn’t so sure this scenario stood much of a chance.

“The question whether it is still possible to bring about an outbreak of creative sanity in mankind, to avert this steady glide to destruction, is now one of the most urgent in the world,” he wrote in a 1921 introduction to the republished book. “It is clear that the writer is temperamentally disposed to hope that there is such a possibility. But he has to confess that he sees few signs of any such breadth of understanding and steadfastness of will as an effectual effort to turn the rush of human affairs demands.”

What we take from H.G. Wells is the nagging suspicion that we are not in control.

By 1946, the year that Wells died, civilization experienced yet another all-nation conflagration — one that included the use of the atomic weapons he had foreseen three decades earlier. Most of us, of course, share few of the aforementioned utopian socialist hopes. What we do take from Wells is the nagging suspicion that we are not in control, that the technologies we so gleefully develop will continuously backfire on us in ever more horrific ways, and that our love of individual freedom is a collective extermination pact.

In this context, “history,” from now on, is the story of how we as a species repeatedly dodge that mass suicide at the last minute, until at last we don’t. That, not his utopian socialism, is the Wellsian vision of the future that we find so compelling — the version told in his novels and made into movies, to be retold in myriad new forms for as long as we survive.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition