And before we judge of them too harshly we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals, such as the vanished bison and the dodo, but upon its inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?

We survive this assault via biological dumb luck. The Martians turn out to be allergic to Earth bacteria, and drop dead. But references to evolution and devolution are all over War of the Worlds, as in the principal characters’ conversation with an “artilleryman” (loosely portrayed by Tim Robbins in the Spielberg film), who gives the protagonist shelter in a house. In the novel, the soldier has all kinds of plans for what do next — first off creating a new society in London’s sewer system.

“We have to invent a sort of life where men can live and breed, and be sufficiently secure to bring the children up,” he explains. “Yes — wait a bit, and I’ll make it clearer what I think ought to be done. The tame ones will go like all tame beasts…. The risk is that we who keep wild will go savage — degenerate into a sort of big, savage rat.”

Sooner or later, someone with better machines but no better values than ours is going to chew us up and spit us out.

The Spielberg version of Wells’ most famous novel doesn’t get very far into these scary philosophical weeds. But like so many cinematic adaptations of his writings, it conveys the feeling that the author wanted us to come away with. As we watch Tom Cruise desperately trying to outrun a huge Martian tripod human scooper, our worst suspicions are confirmed. We are living on technological borrowed time. Sooner or later, someone with better machines but no better values than ours is going to chew us up and spit us out.

That’s pretty close to the message of Terminator Salvation. In the fourth movie episode of the Terminator series, Skynet’s hideous “Harvesters” are, like the tripods, grabbing humans en masse and delivering them to a dark fate at the self-conscious machine networks’ headquarters in San Francisco.

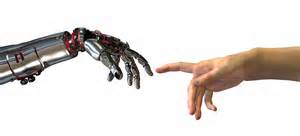

But didn’t humanity have itself to blame for that scenario? Didn’t we create Skynet? H.G. Wells foresaw that special kind of hell too.

A rare first U.S. edition of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, right, differs from a first London edition.

Photo: University of California, Riverside

‘A Great Quiet’

Wells’ 1895 novel The Time Machine is an account of how bad the human race turns out when it blindly mimics the evolutionary model. The protagonist of the story, an English gentleman known only as “The Time Traveller,” uses a miraculous vessel to trek to the year “Eight Hundred and Two Thousand Seven Hundred and One A.D.,” (in his own words). He then describes what he finds to a group of friends when he returns, the equivalent of a week later.

In that A.D. 802,701 future, people have devolved into two groups, he discovers: the “Eloi,” a race of peaceful vegetarians who live on the planet’s surface, and the “Morlocks,” the equivalent of subterranean ranchers, who feed on the Eloi with the assistance of underground machines. Movie versions of the film focus heavily on the Traveller’s relationship with an Eloi named Weena — played by teen movie starlet Yvette Mimieux in the 1960 edition — and his battle with the Morlocks. These films dwell far less on the Traveller’s explanation for how things turned out that way.

It appears that the Morlock/Eloi relationship emerged out of the class divisions of the Traveller’s own epoch, Wells narrates. Human intellect had “committed suicide,” by accepting a comfortable accommodation between the idle rich and mechanically inclined “toiler” classes.

“The rich had been assured of his wealth and comfort, the toiler assured of his life and work,” his Time Traveller explains. “No doubt in that perfect world there had been no unemployed problem, no social question left unsolved. And a great quiet had followed.”

But that “Great Quiet” proved lethal to the human species, which requires trouble and danger to maintain its intellectual versatility and sense of larger purpose.

So, as I see it, the Upper-world man had drifted towards his feeble prettiness, and the Under-world to mere mechanical industry. But that perfect state had lacked one thing even for mechanical perfection — absolute permanency. Apparently as time went on, the feeding of the Under-world, however it was effected, had become disjointed. Mother Necessity, who had been staved off for a few thousand years, came back again, and she began below. The Under-world being in contact with machinery, which, however perfect, still needs some little thought outside habit, had probably retained perforce rather more initiative, if less of every other human character, than the Upper. And when other meat failed them, they turned to what old habit had hitherto forbidden.

‘The Way It Led Me’

Wells described an even more personal version of this mindless fate in his grimmest novel, The Island of Doctor Moreau. In this story, yet another English gentleman, named Edward Prendick, blunders onto a remote island that functions as a biological station for a disgraced vivisectionist. Doctor Moreau, driven from civilization, is now on his own, gleefully carving up wild cats, pigs and dogs, and turning them into strange humanoids, or “Beast People,” with which he lives.

Prendick demands to know how could Moreau justify this behavior.

“You see, I went on with this research just the way it led me,” the physician responds:

That is the only way I ever heard of true research going. I asked a question, devised some method of obtaining an answer, and got a fresh question. Was this possible or that possible? You cannot imagine what this means to an investigator, what an intellectual passion grows upon him! You cannot imagine the strange, colourless delight of these intellectual desires! The thing before you is no longer an animal, a fellow-creature, but a problem! Sympathetic pain, — all I know of it I remember as a thing I used to suffer from years ago. I wanted — it was the one thing I wanted — to find out the extreme limit of plasticity in a living shape.

“But,” Prendick insists, “the thing is an abomination.”

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition