New Scientist – THERE’S a children’s picture book in the US called Brandon and the Bipolar Bear. Brandon and his bear sometimes fly into unprovoked rages. Sometimes they’re silly and overexcited. A nice doctor tells them they are ill, and gives them medicine that makes them feel much better.

The thing is, if Brandon were a real child, he would have just been misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder.

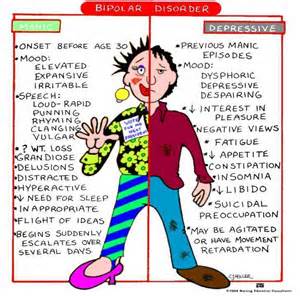

Also known as manic depression, this serious condition, involving dramatic mood swings, is increasingly being recorded in American children. And a vast number of them are being medicated for it.

The problem is, this apparent epidemic isn’t real. “Bipolar emerges from late adolescence,” says Ian Goodyer, a professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Cambridge who studies child and adolescent depression. “It is very, very unlikely indeed that you’ll find it in children under 7 years.”

How did this strange, sweeping misdiagnosis come to pass? How did it all start? These were some of the questions I explored when researching The Psychopath Test, my new book about the odder corners of the “madness industry”.

Freudian slip

The answer to the second question turned out to be strikingly simple. It was really all because of one man: Robert Spitzer.

I met Spitzer in his large, airy house in Princeton, New Jersey. In his eighties now, he remembered his childhood camping trips to upstate New York. “I’d sit in the tent, looking out, writing notes about the lady campers,” he said. “Their attributes.” He smiled. “I’ve always liked to classify people.”

The trips were respite from Spitzer’s “very unhappy mother”. In the 1940s, the only help on offer was psychoanalysis, the Freudian-based approach of exploring the patient’s unconscious. “She went from one psychoanalyst to another,” said Spitzer. He watched the psychoanalysts flailing uselessly. She never got better.

Spitzer grew up to be a psychiatrist at Columbia University, New York, his dislike of psychoanalysis remaining undimmed. And then, in 1973, an opportunity to change everything presented itself. There was a job going editing the next edition of a little-known spiral-bound booklet called DSM – the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

DSM is simply a list of all the officially recognised mental illnesses and their symptoms. Back then it was a tiny book that reflected the Freudian thinking predominant in the 1960s. It had very few pages, and very few readers.

What nobody knew when they offered Spitzer the job was that he had a plan: to try to remove human judgement from psychiatry. He would create a whole new DSM that would eradicate all that crass sleuthing around the unconscious; it hadn’t helped his mother. Instead it would be all about checklists. Any psychiatrist could pick up the manual, and if the patient’s symptoms tallied with the checklist for a particular disorder, that would be the diagnosis.

For six years Spitzer held editorial meetings at Columbia. They were chaos. The psychiatrists would yell out the names of potential new mental disorders and the checklists of their symptoms. There would be a cacophony of voices in assent or dissent – the loudest voices getting listened to the most. If Spitzer agreed with those proposing a new diagnosis, which he almost always did, he’d hammer it out instantly on an old typewriter. And there it would be, set in stone.

That’s how practically every disorder you’ve ever heard of or been diagnosed with came to be defined. “Post-traumatic stress disorder,” said Spitzer, “attention-deficit disorder, autism, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, panic disorder…” each with its own checklist of symptoms. Bipolar disorder was another of the newcomers. The previous edition of the DSM had been 134 pages, but when Spitzer’s DSM-III appeared in 1980 it ran to 494 pages.

“Were there any proposals for mental disorders you rejected?” I asked Spitzer. “Yes,” he said, “atypical child syndrome. The problem came when we tried to find out how to characterise it. I said, ‘What are the symptoms?’ The man proposing it replied: ‘That’s hard to say because the children are very atypical’.”

He paused. “And we were going to include masochistic personality disorder.” He meant battered wives who stayed with their husbands. “But there were some violently opposed feminists who thought it was labelling the victim. We changed the name to self-defeating personality disorder and put it into the appendix.”

DSM-III was a sensation. It sold over a million copies – many more copies than there were psychiatrists. Millions of people began using the checklists to diagnose themselves. For many it was a godsend. Something was categorically wrong with them and finally their suffering had a name. It was truly a revolution in psychiatry.

It was also a gold rush for drug companies, which suddenly had 83 new disorders they could invent medications for. “The pharmaceuticals were delighted with DSM,” Spitzer told me, and this in turn delighted him: “I love to hear parents who say, ‘It was impossible to live with him until we gave him medication and then it was night and day’.”

Spitzer’s successor, a psychiatrist named Allen Frances, continued the tradition of welcoming new mental disorders, with their corresponding checklists, into the fold. His DSM-IV came in at a mammoth 886 pages, with an extra 32 mental disorders.

Now Frances told me over the phone he felt he had made some terrible mistakes. “Psychiatric diagnoses are getting closer and closer to the boundary of normal,” he said.

“Why?” I asked. “There’s a societal push for conformity in all ways,” he said. “There’s less tolerance of difference. Maybe for some people having a label confers a sense of hope – previously I was laughed at but now I can talk to fellow sufferers on the internet.”

Part of the problem is the pharmaceutical industry. “It’s very easy to set off a false epidemic in psychiatry,” said Frances. “The drug companies have tremendous influence.”

One condition that Frances considers a mistake is childhood bipolar disorder. “Kids with extreme temper tantrums are being called bipolar,” he said. “Childhood bipolar takes the edge of guilt away from parents that maybe they created an oppositional child.”

“So maybe the diagnosis is good?”

“No,” Frances said. “And there are very good reasons why not.” His main concern is that children whose behaviour only superficially matches the bipolar checklist get treated with antipsychotic drugs, which can succeed in calming them down, even if the diagnosis is wrong. These drugs can have unpleasant and sometimes dangerous side effects.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition