According to Mouood, quoting buy The National News:

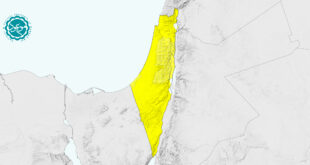

Why is it so hot in the Middle East?

The link between climate change and future conflicts is especially worrying JANINE DI GIOVANNI November 7th 2021, 6:45 AM

When in less than a fortnight Cop26 ends in Glasgow, and the diplomats and climate change experts go home having pledged to end deforestation in 10 years, their thoughts should also turn towards the Middle East, where global warming is occurring faster than the global average.

If last summer was an example, the region could become uninhabitable in the years to come. Temperatures in Kuwait this June reached 53.2°C, a figure unfathomable to some. Iran, Iraq and Oman also reported scorching temperatures.

Then there were blazing fires in forests or in resorts, such as in Turkey’s southern coast; terrible droughts; cities so hot that it was impossible for people to leave their homes. There is also another major worry – the naturally arid Middle East is not best equipped to cope with these fluctuations in temperature.

During a visit to Gaza last August, I noticed the stifling heat was far worse than on any other summer visit I have experienced over the past few decades. When I stepped outside my hotel, the sun was blistering. Car rides were sweltering. The refugee camps, where most of Gaza’s inhabitants live, were unbearable. The World Bank is predicting that for four months a year, the Middle East will face this kind of heat – and it will last for longer periods of time, making some areas uninhabitable.

It’s not too bad if you can afford air conditioning or live in a place where electricity and water are plentiful. But in places such as Gaza, that is next to impossible. Equally vulnerable are the camps and settlements for the millions of displaced people in northern Iraq or the refugees who fled the Syrian war and are still in Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey and Egypt. For the people most at risk, climate change is a tangible rather than an existential threat. It will become increasingly hard to live in some of these places.

Take Iraq as an example. The UN marks Iraq as one of the most vulnerable countries on the planet, where 31 per cent of the surface is desert. Years of inappropriate farming as well as water mismanagement have exacerbated an already dry climate. In areas such as the Nineveh Plain, an important breadbasket, many people rely on farming. Yet the results of climate change are, evident as they are, will be even more disastrous in years to come. It doesn’t help that the Islamic State deliberately damaged irrigation sources when they rolled through in 2014.

The World Bank also cites these kind of drastic temperature rises will cause severe damage to crops. Scare water sources will mean more uninhabitable places. It also means increased migration and the potential for more conflicts arising. Demographic growth puts further strain on resources.

UNICEF gives some grim statistics on how population changes will put more strain on requirements for water and agricultural output. In Iraq, between 1970 and 2007, the population tripled to 30 million. What will access to water be like in the future? Already, 21 per cent of the population has no access to safe drinking water sources. A recent World Bank report cites: “With rainfall projected to decline by 20 to 40 per cent in a 2°C hotter world, and up to 60 per cent in a 4°C world, the region’s capacity to provide water to its people and economies will be harshly tested.”

Can all this lead to more conflict? The evidence points to a bleak future. Several climate change experts are looking at the links between climate change and future conflicts and how they can be prevented. Conflicts escalating because of water rights could rise around the globe, leading to post-apocalyptic sounding “water wars”, where people will fight over water to survive. The Tigris-Euphrates as well as the Nile are both pinpointed crisis areas. And researchers have linked the Syrian conflict to the 2006-2009 drought made worse by climate change. It is one of the strongest links yet that between climate change and human conflict.

So what can be done? The World Bank advises that disaster risk assessments need to be established, and fast. After their 2008-2011 drought, Djibouti began carrying out world’s first Post-Disaster Needs Assessment. They set up more risk-management laboratories and knowledge centres, which teach people how to manage the crisis – as well as investing in protective infrastructure. Djibouti also rehabilitated the dyke that protected people from a flood-prone wadi. It has also performed seismic and floods risk/vulnerability assessments and established a flood early warning system.

These kind of centres should be established throughout the region, and the UN should help out, too – by expanding their Green Climate Fund to the more vulnerable parts of the Mena region, especially when it comes to water, agriculture and food scarcity.

The biggest worry for the Middle East is that climate change can make some governments less equipped to handle civil unrest. This may be true even for countries that are resource-rich but poorly governed, such as Libya. Over the past decade, militias have been fighting to control the oil infrastructure amid a raging civil war.

At one point, we assumed climate change would be too far in the future. We now know it is a matter of decades – and in the Middle East, we are already feeling the impact.

Policies adopted today – as a result of global gatherings such as Cop26 – can begin to reverse that. Let’s hope when the dust settles from the Glasgow conference, the Middle East will be a priority.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition