The Art of Sanctions – On the Search for Inflection Points:

in the preceding chapters, we examined sanctions pain and resolve in isolation, identifying ways to classify and weigh the factors that go into these critical elements of leverage that both sides bring to a conflict. We also considered the case of Iran as it progressed. In this chapter, we will examine the effort to find intersection of these two forces, which ultimately is the trick of a sanctions campaign: subjecting a country to such pain that it concedes as swiftly as possible and modifies its behavior in a mutually acceptable (if not ideal) manner.

Mouood’s Introduction: The author of the present book (The Art of Sanctions) is Richard Nephew. Richard Nephew was in charge of the sanctions team against Iran during Obama’s second term. He supported the nuclear negotiators in the matter of sanctions in Vienna. Richard Nephew has previously served for ten years as an Iran member of the National Security Council at the White House and as Deputy Secretary of State for Coordination of Sanctions at the State Department. The book is also translated into Persian by the Iranian Parliamentary Research Center (IPRC).

Note: The content of this book is not approved by us and is published solely to familiarize policymakers with the views, approaches, and methods of the designers of sanctions against Iran.

I contend the JCPOA constitutes such an intersection of pain, resolve, and opportunity for a sanctioned country to get off the hook.

Reaching the “goldilocks” inflection point of effective sanctions pressure and resolve changes requires the development of a strategy for applying pain. Flowing from the issues discussed in prior chapters, I believe that it is necessary to design and implement sanctions following a framework introduced in the introduction and restated here. A state must

- identify objectives for the imposition of pain and define minimum necessary remedial steps that the target state must take for pain to be removed;

- understand as much as possible the nature of the target, including its vulnerabilities, interests, commitment to whatever it did to prompt sanctions, and readiness to absorb pain;

- develop a strategy to carefully, methodically, and efficiently increase pain on those areas that are vulnerabilities while avoiding those that are not;

- monitor the execution of the strategy and continuously recalibrate its initial assumptions of target state resolve, the efficacy of the pain applied in shattering that resolve and how best to improve the strategy;

- present the target state with a clear statement of the conditions necessary for the removal of pain and an offer to pursue any negotiations necessary to conclude an arrangement that removes the pain while satisfying the sanctioning state’s requirements; and

- accept the possibility that, notwithstanding a carefully crafted strategy, the sanctioning state may fail because of inherent inefficiencies in the strategy, a misunderstanding of the target, or an exogenous boost in the target’s resolve and capacity to resist. Either way, a state must be prepared either to acknowledge its failure and change its course or accept the risk that continuing with its present course could create worse outcomes in the long run.

In the simplest abstraction, we can imagine a scenario in which a sanction is applied, a target responds, and after one or two moves, the situation resolves itself as amicably as possible in these circumstances. One or both sides arrange for a climb-down by one or both sides, allowing for a settlement (permanent or not) and the removal of sanctions and establishment of a new normal.

In fact, a survey of sanctions history—provided courtesy of Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliott—would argue in support of the notion that this is the prevailing pattern for sanctions implementation, with many modest sanctions regimes being imposed throughout the twentieth century and in short order being dismantled.

But the toughest cases rarely resolve themselves so neatly. This may be because sanctions are an altogether inappropriate tool to use in the situation at hand. However, basic neglect to adhere to a strategic framework in applying sanctions may also be involved, leading to the three most common causes of sanctions failure: under-reach, over-reach, and confused objectives.

Under-Reach

Sometimes, despite a sanctioner’s best efforts, the imposition of sanctions does not generate the pain necessary to prompt a policy change. In fact, this is the base case for the imposition of sanctions pain until an inflection point is reached: sanctions imposition proceeds along its defined route, adding pain and inflicting damage along the way. And, at some stage, a switch is flipped and the state receiving the pain takes whatever step is necessary to prevent further pain.

However, there are some sanctions initiatives that never fulfill their objectives and modify the opposite state’s behavior. An example of this could be the aforementioned Iranian decision to impose reciprocal sanctions on primarily European antagonists from 2006 to 2013. This step may have had political value at home, but from the standpoint of affecting the strategy of the sanctioned party—in these cases, to get them to withdraw the sanctions that they were applying against Iran—these sanctions were dismal failures.

Why they failed is an interesting question. The problem probably lies in the inadequacy of the sanctions imposed. The European economy was not sufficiently impinged in either case to prompt or justify policy reconsideration. Logically, this would argue in favor of Iran escalating their sanctions force in order to have the political impact desired. Yet, it did not do so. Instead, Iran continued to sell oil to and buy other things from Europe.

Two interlocking judgments are logical explanations for this outcome. The first is that Iranian officials assessed that their escalation of sanctions would diminish the readiness of Europe to stay the course and reject even tougher sanctions pushed upon them by the United States. From the policy statements made by European leaders on the Iranian file to the simple economic realities concerning the relative economic weight and opportunities available to Europe, it was apparent to many outside observers, and surely Iranian policymakers, that European resolve was unscathed and would remain so.

But, for so long, neither was Europe prepared to abandon Iran altogether, choosing a middle course. An exaggerated Iranian sanctions campaign could have tipped this balance and away from Iran’s own interest to retain some trade ties and relationships.

The second explanation is that the leaders of Iran understood that their country would be the worse for further escalation. From a compromised economic position, they determined that their own commitment in sustaining the application of pain against Europe would diminish over time, potentially undermining their ability to achieve a marginally better diplomatic solution. Consequently, rather than engage in a pointless and costly escalation, both took the more pragmatic and cautious route.

In abstract terms, the failure of a sanctions regime to achieve its initial objectives should logically prompt a reconsideration of those objectives by the sanctioning state. The question then becomes whether the sanctions endeavor is itself misguided or whether the tools are simply insufficient. As noted above, if a sanctioning party decides that the strategy may yet be successful if the sanctions regime is expanded, modified, or retargeted, then under-reach has yet to be “achieved”; rather, the reevaluation point simply becomes a bump in the road for the sanctions policy being implemented.

On the other hand, a sanctioning party may decide that the strategy is fatally flawed and instead either modify it to employ new, tougher tools (such as military force) or change its objectives to align the existing tools with more plausible objectives. This reappraisal by the sanctioning state does not require a formal policy review, though it may involve one. Instead, it can merely begin with a leader’s growing appreciation that the chosen path is not going to work.

Over-Reach and Unintended Consequences

Sanctions over-reach occurs when sanctions have been so onerous as to push the sanctions target to either double down on its existing, objectionable conduct or to escalate. Sanctions over-reach is a more complicated topic than sanctions under-reach, in part because it is less provable. Under-reach can be identified by the sanctions target’s failure to change course. By contrast, over-reach can be easily argued by sanctions proponents and objective observers alike to be a manifestation not of an incorrect approach to sanctions but rather of the aggressive nature of the sanctions target. Just as with sanctions under-reach, the argument goes that sanctions “failed” because sanctions were an insufficient barrier to bad conduct—not that sanctions themselves prompted bad behavior.

But this mindset suggests that sanctions targets are not justified in seeing the imposition of sanctions as violence being inflicted against them by sanctioners. It substantiates a view—which I believe is wrongheaded—that sanctions are not strategically applied force but rather purely defensive measures applied by a sanctioning state to defend itself. As I have written about elsewhere, this argument is belied by both the rhetoric surrounding sanctions and the nature of the tools themselves and how they are implemented. [1]

If one instead thinks of sanctions as an instrument of force, then it is easy to understand how over-reach can occur and why the response to it can, at times, transcend economic or political means.

This is particularly the case when the application of sanctions is so damaging as to risk the primary motivations or interests of the target. A classic example of this is the imposition of the U.S. oil embargo against Japan in the 1930s. Some commentators have argued that this action led the Imperial Japanese government to fear for its economic survival and, in time, to attack Pearl Har-bor in 1941. [2] For the United States, however, the embargo was a signal of resolve and warning to Japan, while it simultaneously choked off a supply of vital materiel for the Japanese war effort.

What the United States failed to understand is that Japan saw this action as itself a casus belli. A similar argument can be made to the over-reach of economic force against Germany during the interwar period, albeit in the form of “reparations.”

Of course, the problem with the possibility of sanctions over-reach is that it argues for restraint on the part of sanctioners if there is a chance that the sanctioned party will overreact. Yet, the power of sanctions depends—at least in part—on the perceived threat of escalation on the part of the sanctions target. If targets believe things can get better or if they can accommodate themselves to the pain, then sanctions lose their potency.

To some extent, the challenge faced by sanctioners is the same as those facing their military counterparts in the conduct of a limited war. Without the specter of complete annihilation to compel capitulation, sanctions targets may be less willing to compromise in the short term, prolonging the crisis and the conflict. With that specter, then it is possible the sanctions target will instead mount a counteroffensive that exceeds the risk tolerance of the sanctioner or—worse—respond in other ways, just as the Japanese did in 1941.

There is no hard-and-fast trick for divining when sanctions may transcend their intended level of distress and become instead a trigger for the target state to lash out. Rather, success lies in a careful examination of the interests of the target and in knowing how far to push. The approach suggested with respect to measuring resolve is also helpful here, as the sorts of analysis required to understand whether a target is about to fold can also point to indications that a target is about to instead escalate the situation.

But, ultimately, it is this possibility that ought to make sanctions proponents pause in their advocacy.

Another risk from sanctions over-reach is the creation of unintended (and, ultimately, unproductive) pain for the sanctions target.

Any foreign policy action carries with it some risk of unintended consequences. These consequences can have a strategic flavor: for example, that the decision to undertake one military mission deprives a force of the ability to undertake another, even if the second mission is more vital to the future of the state in question.

Sanctions too can share this risk: using sanctions to reduce the ability of one major oil exporter to put oil on the market means that the market itself is less able to weather the withdrawal of another oil producer’s share.

But in sanctions, the unintended consequence most frequently cited is that of humanitarian suffering. As described in chapter 2, “Iraq in the 1990s” has become the poster child for the concept of sanctions imposing undue humanitarian consequences, with hundreds of thousands of Iraqis bearing the brunt of the economic deprivation imposed as a result of sanctions and Iraqi government policy in response to them.

Even sanctions regimes with humanitarian carve-outs can contribute to humanitarian problems because of the broader effects of the measures selected. In Iran, for instance, there were reports throughout 2012 and 2013 that medicine and medical devices were unavailable not because their trade was prohibited but rather because they cost too much for the average Iranian due to shortages and the depreciation of the Iranian currency. [3]

The United States and its partners, through sanctions, directly contributed to the depreciation of the Iranian rial and, consequently, played some part—even if unintentional— in the creation of this problem.

Sanctions over-reach of this sort is not merely an issue for aid workers. Misdirected sanctions pressure can also undermine the utility of a sanctions regime by stiffening resolve (aiding the government targeted to pin the blame on an outside other rather than accept the blame for its own misdeeds) and create a vicious cycle of deepening resentment toward the outside world. Sanctioners should be wary of—and responsive to, where possible—indications that their sanctions regime is having significant unintended consequences because these effects could be counterproductive in both the short and long term.

The U.S. effort to target Iran via the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is an instructive case in point. From 2006

to 2010, much of the U.S. strategy was to identify the litany of misdeeds undertaken by the IRGC and to extrapolate from there a basis to isolate Iran economically. The approach was straightforward (and aided by Iranian conduct): show that the IRGC was a bad actor and urge partners to forbid any economic activities with it or its proxies.

In time, this strategy took on additional elements. Legally, the United States decided that any significant transactions with the IRGC and its associates merited being cut off from the U.S. financial system (via the 2010 Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability and Divestment Act [CISADA]).

Diplomatically, the United States broadened the sweep of its condemnation of the IRGC, adding it to a variety of different sanctions lists, with elements designated under U.S. law for violations of human rights, actions in Syria, testing of ballistic missiles, and so forth. The IRGC, already powerful in Iran domestically, was also portrayed by Washington as being at the center of all Iranian government conduct.

Again, this claim had a factual basis. But the intent of the U.S. strategy was to make the IRGC and Iran inseparable concepts with the aim of chilling even still legal forms of business with Iran under the precept that no one could know outside Iran whether the IRGC was involved in or the beneficiary of transactions at a deep level.

Although U.S. sanctions targeted the IRGC explicitly, the IRGC arguably grew stronger during this period. Why? I believe two factors explain this situation. The first is that IRGC officers were in a good position to capitalize on the inherent corruption of the Iranian economy that was enriched by a negligent Ahmadinejad administration of 2005 through 2013. They possessed the connections and the wealth to place themselves at the center of the Iranian economy, using available funds to take significant if not controlling stakes in a variety of Iranian economic concerns. Second, ironically, U.S. sanctions and hostility toward the IRGC

forced the Iranian system both to rely upon and to support the IRGC. The IRGC was a primary means whereby Iran could procure sensitive items otherwise prohibited under sanctions, making the IRGC once more heroes to the Iranian government and the economic beneficiaries of their smuggling enterprise. For this reason, as Iran grew poorer and more vulnerable to economic pressure, the IRGC grew stronger.

This reality has made JCPOA implementation especially difficult because international business cannot escape the possibility that sitting at the other end of even legitimate transactions was a very illegitimate actor. Even under the JCPOA, the IRGC is not due to be removed from U.S. sanctions, exposing non-Iranian business to the risk of being punished for violations of U.S. sanctions.

For this reason, the U.S. Department of the Treasury took the somewhat extraordinary step of indicating that even transactions with IRGC-controlled entities might not necessarily be sanctionable during an update to standing legal guidance in late 2016.

However, as a Reuters analysis showed in January 2017, the beneficiaries of many foreign deals with Iran under the JCPOA still involved the IRGC at some level. [4]

Predictably, this has led to charges that while advocates of the JCPOA hoped it would lead to economic openness in Iran that is counter to IRGC and state-level control, the opposite has proven true, at least in the short term. Given the hostility and fear that—again, justifiably—still surrounds the IRGC in the United States and broader international community, it can be safely concluded that the U.S. sanctions focus on the IRGC in the early period of enforcement did little to damage the IRGC.

Instead, it may have contributed to lagging implementation of the JCPOA. Worse, since the IRGC’s response to sanctions was to place itself more at the center of Iranian affairs, the U.S. approach toward the IRGC ultimately could have helped reinforce the IRGC’s grip over the country.

Importantly, this was not a surprise to many analysts looking at Iran from 2006 to 2016, including some in the U.S. government. Ultimately, the exigencies of the situation forced this kind of strategy on the United States and its partners. Indeed, while it is possible that an IRGC sanctions focus may have limited the sanctions relief of the JCPOA to Iran, it is also possible that a different sanctions approach may have failed to generate the pressure necessary to achieve the JCPOA.

My aim with this observation is not to suggest that the United States should have chosen a different approach to the sanctions regime in 2006–2010 but rather to underscore the point that second- and third-tier implications from sanctions actions are sometimes difficult to predict. Given this, the unintended consequences of sanctions merit considerable study both in academia and by sanctions practitioners. They should observe the IRGC situation and keep it in mind as they develop future sanctions regimes.

Confused Objectives

In the previous sections, I make a prevailing assumption: that the sanctioner pursues a uniform, commonly understood set of objectives. In many cases, this is probably true. The sanctioner may not be able to achieve its goal, but it knows what it is trying to do and—consequently—has a clear set of thresholds that sanctions help it cross.

But this is probably not universally true, and the cases of Iraq and Iran neatly demonstrate this particular problem. For Iraq, the goals identified at the start of the sanctions campaign were straightforward: end Iraq’s ability to threaten its neighbors with weapons of mass destruction and prevent further aggression from Saddam Hussein.

Over time, the objective shifted: it was no longer acceptable to contain Saddam Hussein—in part because of fears that the sanctions regime might fade away—because he was deemed uncontainable. Instead, the only acceptable objective that could be attained was Saddam’s removal from power. By realizing this objective, Iraq would be able to once more become a trust-worthy nation. As a result, the ultimate goal of defanging Iraq would be achieved.

The problem is that sanctions pressure—even combined with the threat of force—was insufficient to motivate Saddam to depart Iraq before hostilities were begun in March 2003. The shifting objectives of sanctions—from containing the menace that Iraq could become to ensuring that it would never be in a position to menace its neighbors—simply increased the burden that sanctions pressure and the threat of force were forced to bear.

And, by setting the bar so high, U.S. and partner decision makers almost ensured that nonmilitary means to achieve the goal would be a failure, particularly when it became apparent that the pressure the United States and partners sought to apply on Saddam Hussein simply was being shrugged off through sanctions evasion and Saddam’s deliberate lack of concern for the plight of his population.

With Iran, a similar murkiness clouded deliberations over the goals and related objectives of the nuclear-related sanctions campaign. In its most direct formulation, the U.S. goal was for Iran to be prevented from producing or acquiring a nuclear weapon. That Iran would have a latent nuclear weapons capability was ensured by its successful operation of a uranium centrifuge facility during the last years of the George W. Bush administration. Iran would be capable, even if its existing facilities were destroyed, of resurrecting its nuclear weapons program at a time and place of its choosing.

I would argue that the George W. Bush administration was not solely responsible for Iran’s standing at the nuclear precipice and that, as outlined in chapter 3, Iran achieved a significant degree of latency with its clandestine acquisition of uranium centrifuges in the late 1980s and illicit experiments with them in the 1990s. The task for the George H. W. Bush, Clinton, George W.

Bush, and Obama administrations was to seek a solution for Iran’s nuclear program that kept it from physically developing nuclear arms and from politically deciding to pursue them.

By 2009, a healthy debate had emerged in Washington, as well as in capitals throughout the Middle East, as to whether this established goal could be achieved through nonmilitary means. There were advocates for and against, with perspectives ranging from a conviction that, even if sanctions compelled Iran to make concessions, Iran could never be trusted with any form of nuclear program because the risk of its cheating was too strong. This debate also involved a more fundamental question about the nature of the Iranian government.

Some passionately believed (and many still believe) that the present system of Iranian government is incompatible with good relations with the West or its regional neighbors. To varying degrees, they believe that regime change in Iran is a necessary precondition of a sustainable Middle Eastern security and political order, and that a change in the Iranian government would be better for the Iranian population, as well. For the analysts and politicians of this school of thought, sanctions were a vital component of a broad strategy for confronting Iran’s full range of bad behavior.

Until and unless each constituent element of that bad behavior was resolved, a negotiated solution involving sanctions relief for Tehran was inherently suspect. Some in this camp may have been prepared to accept modest modifications to U.S. sanctions policy, mindful of Iranian politics.

Others may have been prepared to acknowledge that some fundamental elements of Iranian policy would remain unchanged in any deal negotiated. For example, they might have acknowledged that the internal Iranian human rights situation may not improve as a result of a nuclear deal but that—in addition to addressing issues around the Iranian nuclear program—Iran must make an accommodation with respect to its support for Hezbollah in order to receive sanctions relief.

By contrast, others—including the Obama administration, in general—accepted a different logic. It started with certain assumptions about the problem facing the United States and its partners, and the likelihood of sanctions—or, for that matter, external pressure as a general matter—changing Iranian policies and practices across the board. For these analysts and politicians, it was necessary to have a more constrained vision for what sanctions could do and what U.S. policy could achieve. Few, if any, of these individuals would offer any acceptance of Iran’s range of destructive and loathsome activities.

Most, in fact, would freely stress their opposition to Iran’s behavior in this regard. But they had a different understanding of what the sanctions regime assembled from 1996–2013 was intended to achieve and what was possible even under ideal circumstances. Consequently, they had another vision for the JCPOA and a different way of gauging its success.

Moreover, some (me included) argued that a different strategy, with economic and political engagement at its core rather than isolation, would be more effective in addressing Iran’s internal political and human rights situation and that different tools (like maritime interdictions) would be more successful in controlling Iran’s support for terrorism abroad.

For a while, the combination of threatened U.S. military force and a largely unified, global approach to sanctions papered over this debate, as everyone in Washington (and beyond) opposed to Iranian nuclear weapons development could find something in the U.S. and partner strategy to latch onto. This papering over was facilitated by a holistic approach to sanctions, with measures imposed against Iranian individuals and entities for a variety of bad acts. In some cases, as with the IRGC, certain entities were targeted multiple times via multiple legal instruments, even if they had overlapping penalties.

By throwing the book at the IRGC and others in Iran, the strongest case possible was made that Iran’s many bad acts merited international isolation. However, although it made sense at the time, this was a tactical mistake on the part of the Obama administration and one that helped create the problems that emerged with the negotiations effort from 2013 to 2016.

In my view, this debate re-erupted with the JCPOA because the objectives of the sanctions strategy were confused and obscured.

Each side in the debate, both for the deal and against it, could argue that the other side was misunderstanding the purpose of the sanctions effort and come to a different conclusion as to whether sanctions relief in the JCPOA was appropriate. This became doubly complicated when it became apparent that, in addition to confused objectives, there was a difference in analysis as to how far sanctions could push Iran to make concessions. For some, the sky was the limit. Others accepted the limited—though real—utility of sanctions power against Iran.

Ultimately, the debate crystallized around supposition from all sides, argued in a polarized political environment. No one can be proven right, in part because all sides are arguing counterfactual points on the basis of their analysis of an uncertain future.

But these competing views of reality must be reconciled if there is to be an acceptable basis of fact on which to evaluate such an important policy decision as the JCPOA despite the myriad objectives pursued. The question is not whether the JCPOA itself is good; rather, the question is whether additional pressure could have gotten something “better,” defined here as an increase in the scope, duration, or severity of the restrictions in place against Iran under the JCPOA or modifications to its broader range of illicit activities.

Proponents of the JCPOA assert that that more sanctions pressure would not have resulted in a better deal if it were even possible to create such pressure. As I noted in earlier chapters, many proponents argue that, at the time JCPOA negotiations were commenced, sanctions pressure against Iran was beginning to wane and expectations in the country had improved.

Much of the reasoning for this judgment is tied to the election of President Hassan Rouhani in June 2013 and his appointment of a range of technocratic experts to govern the country. But part of the reasoning stems from the plateau that sanctions pressure had apparently reached by fall 2013.

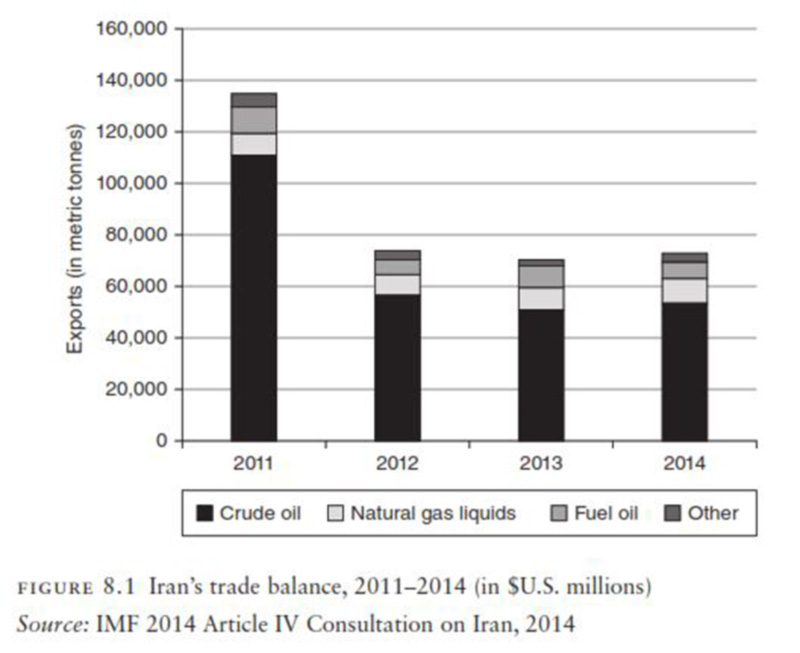

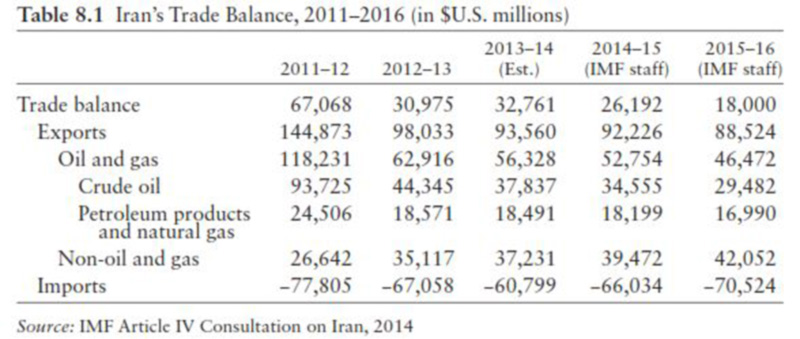

A variety of indicators support this contention, which even opponents of the JCPOA have acknowledged to some extent (at a minimum, in their insistence in fall 2013 that sanctions be intensified). Three indicators worth outlining here are: the increased stability of Iranian oil exports, albeit at a significantly lower level than in 2011 and previous (captured in figure 8.1); increase in non-oil trade with Iran (captured in table 8.1), albeit not at a sufficient rate to make up for lost oil revenues; and the efficiencies achieved as a result of reforms undertaken prior to 2013—such as reduced subsidies for and price controls over energy products—and what was planned insofar as future privatization.

The pain expectation for proponents of the JCPOA, therefore, did not stay in a plateau: it started to drop. The expectation among policy makers is that it would do so absent the kind of embargo placed on Iraq in the 1990s and possibly with the same sorts of consequences. Policy makers were also concerned with the risk of sanctions fatigue sapping support behind the policy and Iran receiving the benefit of sanctions relief for free. Plain economics were a part of this calculation in addition to strategy: at the time negotiations started with Iran in 2013, oil was still trading at more than $100 per barrel.

But proponents of the JCPOA did not merely argue that the application of pain could not be intensified; they also contended that opponents of the JCPOA misunderstood the intensity of Iranian resolve. This argument focused on three themes: first, Iran was prepared to accept considerable hardship in defense of its nuclear program, which had become a national treasure;

second, Iran believed that it could outwait the United States and its partners, reducing its incentive to negotiate and increasing its incentive to build facts on the ground with new centrifuge installations;

and third, the degree to which Iran is incapable of compromising with its hated American enemy, particularly on issues associated with its regional and domestic policies. These three factors combined to create a resolve perspective in Iran that was intrinsically opposed to capitulation in negotiations and, thereby, a limit to how far Iranian negotiators would be prepared to go.

Proponents of the JCPOA argued that it was possible that additional pressure could create a better JCPOA, but that it was unknown if and how much more pressure would be required to overwhelm Iranian resolve. And, to boot, opponents were unable to articulate what kind of negotiated outcome Iran could reasonably be expected to support that would meet the standards demanded by those in opposition.

Still, opponents of the JCPOA, by contrast, expressed confidence that the inevitability of economic decline in Iran would force further concessions on the part of Iranian negotiators, if not immediately, then in time, given Iranian worries about domestic unrest from continued sanctions pressure.

Ironically, both proponents and opponents of the JCPOA drew confidence in their positions from a common conclusion that pressure had an impact; the questions became how much more impact could be achieved and to what end.

Opponents, however, did not acknowledge the degree to which this approach failed in Iraq. It was on this basis that the Obama administration argued military conflict probably would result from failing to accept the JCPOA when negotiations concluded: Iran’s resolve to prevent full restrictions on its nuclear program would generate an inevitability for war, as was the case in Iraq.

Iranian refusal to cooperate would signal bad intent for the long term, which further restrictions might not address. Only regime change and military action could achieve the desired results of full assurance. This point is particularly crucial, as it formed another crux of the debate: the established risk tolerance of future Iranian nuclear pursuits of opponents to the JCPOA was so low as to create an impossible standard for negotiations, just as it was with Iraq in 2003.

The logic of their own positions would force, in all but the most inconceivable scenarios of Iranian capitulation, a conclusion that Iran had not conceded enough in order to be trusted. And, for this reason, their opposition was seen to be less on the merits of the JCPOA or the sanctions regime that helped create it, and more on the entire concept of a negotiated outcome.

Measuring levels of pain and resolve therefore took on significance that was not hitherto experienced in sanctions-related debates. Prior to the Iran deal, many sanctions cases resulted in the petering out of sanctions pressure prior to either collapse of the sanctions regime or onset of military force. Otherwise, it resulted in a dramatic escalation into military force after a short time. Here, in the Iran case, was a rare event: the negotiated conclusion of a cease-fire in which weapons were not fired.

But in a normal cease-fire, there is clarity as to the nature of the stakes facing antagonists; with the Iran deal, the picture was (and is) cloudier.

Goldilocks

The strategy of sanctions rests on a fundamental pillar: that a combination of pressures can be applied on a state to overcome its resistance and get it to change its policy.

It is difficult to identify the point at which sanctions pressure and target resolve are sufficiently balanced to create the compromises and concessions sought. The difficulty lies in part because the risk of sanctions under-reach and over-reach remain tied to the perspective of the sanctioning jurisdiction. But it is also because there will always remain imperfection in the information available to both sanctioner and target, as well as in their analysis in how the situation will progress absent a resolution. Assuming there is a moment (or, more likely, moments) in which resolve and pain are balanced and it is advantageous to cut a deal for both sides, the task is to analyze how resolve and pain interact.

The existence of such a perfect “inflection point” revolutionizes analysis of the relationship between sanctioner and sanctioned, making their competition a battle of time, resources, and will. For the sanctioner, the game becomes increasing pain to reduce resolve as swiftly as possible. For the sanctioned party, the endeavor naturally becomes keeping its resolve from draining away. Both have several options available to them to pursue such a strategy—from enlisting partners to targeting vulnerabilities in the target economy or sanctioner’s legal regime—but the precise tools are less important for us to consider at this stage. It is merely sufficient to accept that they exist and will be employed.

It is here that the framework we’ve been building is so important, as it gives the sanctioner the clearest picture possible of the interests, desires, vulnerabilities, and weaknesses of its targets.

It permits a sanctioner to assemble a profile of its target, highlighting those points and identifying means to do damage to the target. It suggests how much time should be allotted for sanctions to do their work and to what degree the use of time itself as a weapon may be effective (such as in the oil-reduction effort against Iran) and to what degree allowing time to pass could eventually undermine the sanctions regime (as the oil reduction effort against Iran may have become absent the negotiation and implementation of the JPOA).

Done properly, it also identifies areas to hit and to avoid, either because applying pain would be counterproductive or meaningless for the final result, just as someone skilled in martial arts can identify pressure points and render their opponent defenseless.

This latter point is a crucial element in particular of the targeted sanctions movement, which probably has not gotten enough credit from those concerned about the humanitarian implications of sanctions. True, even targeted sanctions can eventually cause humanitarian problems. For example, the aforementioned rise in chicken prices in Iran was not exclusive to poultry but affected all manner of agricultural and medical goods, in addition to run-of-the-mill consumer products.

Inflation can be modulated with price controls, but, absent that, it tends to strike a variety of goods equally. Sanctions that aim to increase inflation de facto aim to increase costs to average citizens. But with targeted sanctions, the goal of shifting an adversary’s policy is modulated with a desire to do so in the most efficient and effective manner possible.

This did not occur with Iraq in the 1990s but largely did take place in the case of Iran. Whether the analytical framework developed and considered here can be applied to this end in other cases is the subject of the next chapter.

Footnotes:

1. Richard Nephew, “Issue Brief: The Future of Economic Sanctions in a Global Economy,” May 2015, https://gallery.mailchimp.com/20fec43d5e 4f6bc717201530a/files/Issue_Brief_The_Future_of_Economic_Sanctions _in_a_Global_Economy_May_2015.pdf.

2. Daniel Yergin, The Quest (New York: Penguin, 2012), 233.

3. International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, A Growing Crisis: The Impact of Sanctions and Regime Policies on Iranians’ Economic and Social Rights (2013), 143–51, https://www.iranhumanrights.org/wp-content/uploads/A-Growing-Crisis.pdf.

4. Yeganeh Torbati, Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, and Babak Dehghanpisheh, “After Iran’s Nuclear Pact, State Firms Win Most Foreign Deals,” Reuters, January 19, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-contracts-insight-idUSKBN15328S.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition