According to Mouood, quoting by Pewresearch:

3. Jewish practices and customs

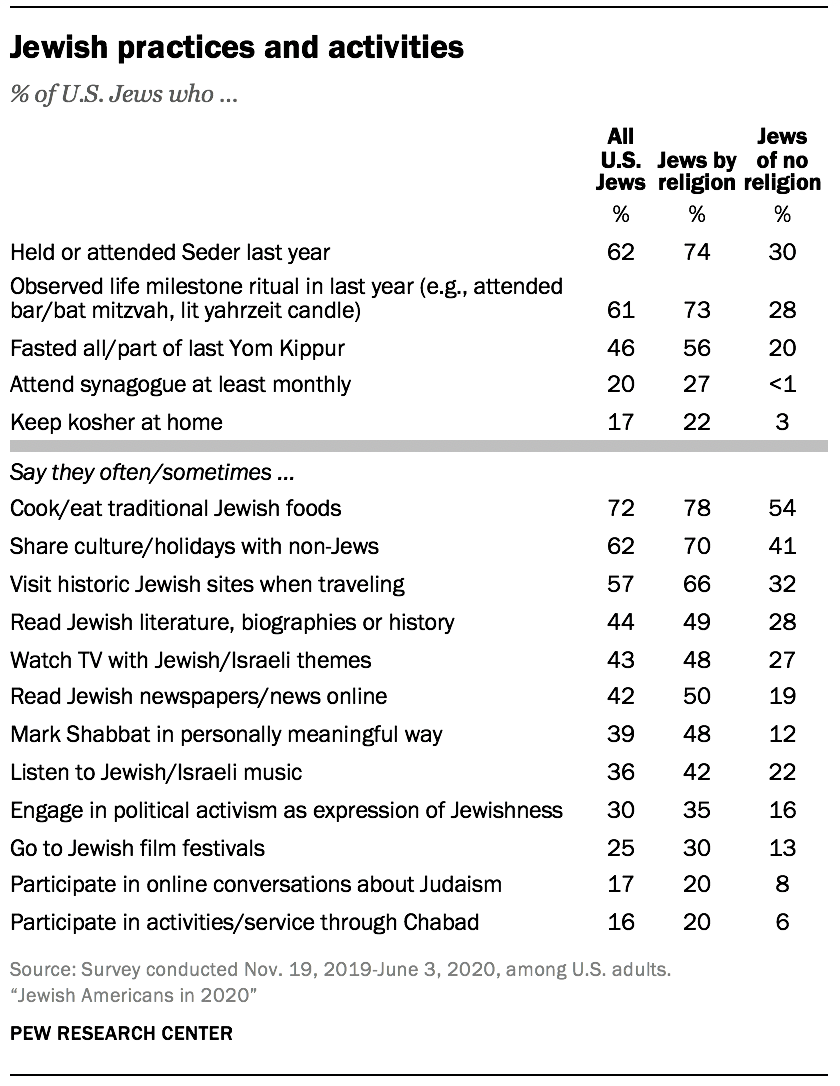

Jewish Americans are not a highly religious group, at least by traditional measures of religious observance. But many engage with Judaism in some way, whether through holidays, food choices, cultural connections or life milestones.

Jewish Americans are not a highly religious group, at least by traditional measures of religious observance. But many engage with Judaism in some way, whether through holidays, food choices, cultural connections or life milestones.

For instance, roughly seven-in-ten Jews say they often or sometimes cook or eat traditional Jewish foods, making this the most common form of engagement with Jewish life among a wide range of practices and activities measured in the survey. And six-in-ten say they at least sometimes share Jewish culture and holidays with non-Jewish friends, that they held or attended a Seder last Passover, or that they observed a Jewish ritual to mark a lifecycle milestone (like a bar or bat mitzvah) in the past year.

Just one-in-five U.S. Jews say they attend religious services at a synagogue, temple, minyan or havurah at least once or twice a month, compared with twice as many (39%) who say they often or sometimes mark Shabbat in a way that is “personally meaningful” to them.

When Jews who do not attend religious services regularly are asked why they don’t attend more often, the most commonly offered response is “I’m not religious.” A slightly smaller majority cite lack of interest as a reason for not attending more often, and more than half of non-attenders say they express their Jewishness in other ways. Among Jews who do attend religious services regularly, about nine-in-ten say they do so because they find it spiritually meaningful.

This chapter explores these and other questions about participation in Jewish life in more detail.

Holidays and milestones

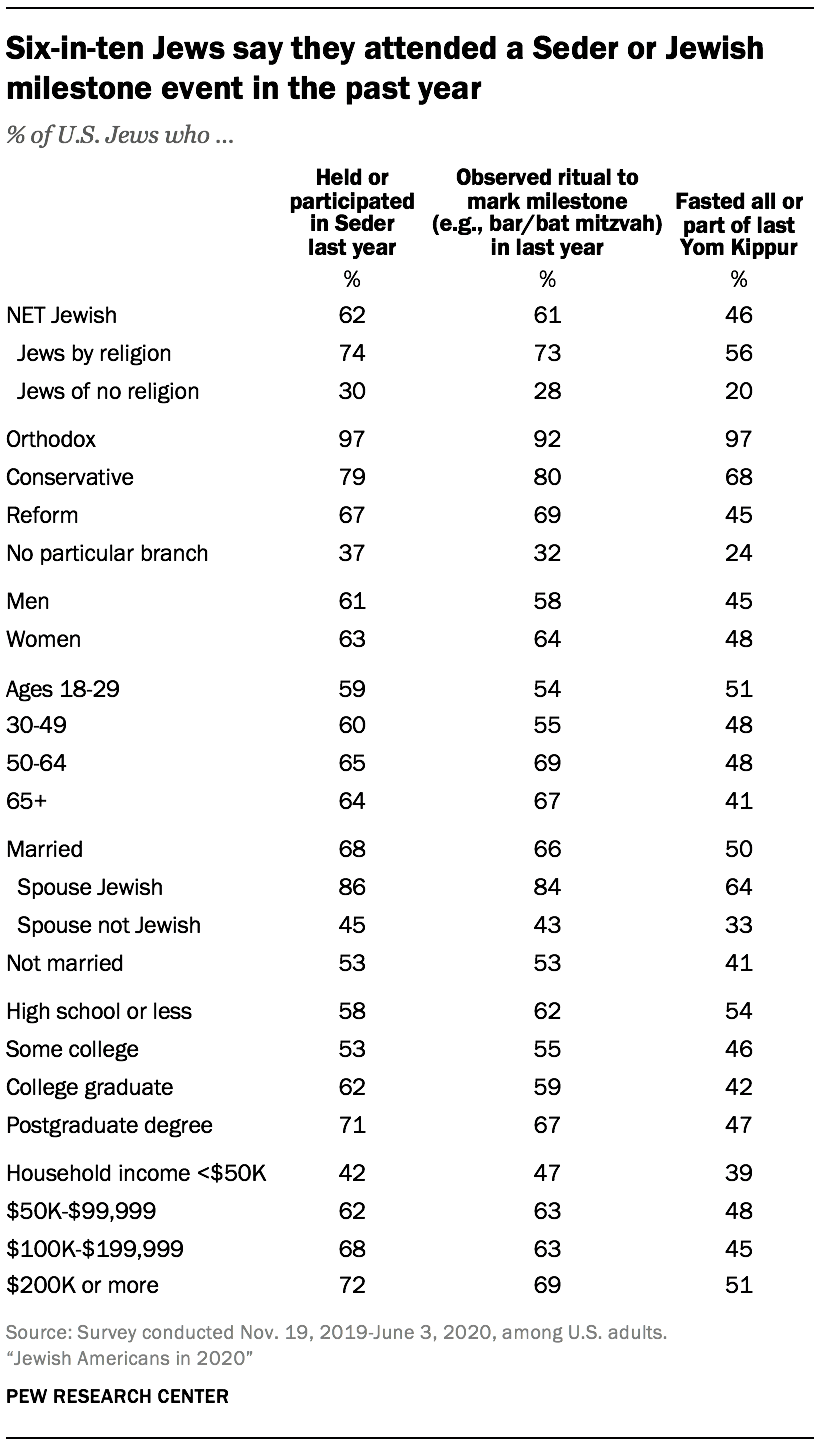

Six-in-ten U.S. Jews say they held or participated in a Seder in the year prior to the survey, and a similar share say they attended a ritual to mark a lifecycle passage or milestone, such as a bar mitzvah or bat mitzvah. Somewhat fewer (46%) say they fasted all or part of Yom Kippur.

Six-in-ten U.S. Jews say they held or participated in a Seder in the year prior to the survey, and a similar share say they attended a ritual to mark a lifecycle passage or milestone, such as a bar mitzvah or bat mitzvah. Somewhat fewer (46%) say they fasted all or part of Yom Kippur.

Respondents who are Jewish by religion are far more inclined than Jews of no religion to participate in these kinds of activities. And Jews with spouses who are also Jewish are more likely than intermarried respondents to have taken part in a Seder, fasted on Yom Kippur and gone to a ritual like a bar or bat mitzvah in the past year.

Jews under the age of 50 are less likely than older Jews to have participated in rituals to mark life cycle milestones. But the youngest Jewish adults (under age 30) are more likely than the oldest Jewish adults to have fasted on Yom Kippur. (Those who cannot fast for health reasons are not obligated to do so.)

Orthodox Jews are more likely than those in other streams (or in no particular branch) of U.S. Judaism to have participated in a Seder, fasted on Yom Kippur, and engaged in a Jewish ritual to mark a life milestone.

Orthodox Jews are more likely than those in other streams (or in no particular branch) of U.S. Judaism to have participated in a Seder, fasted on Yom Kippur, and engaged in a Jewish ritual to mark a life milestone.

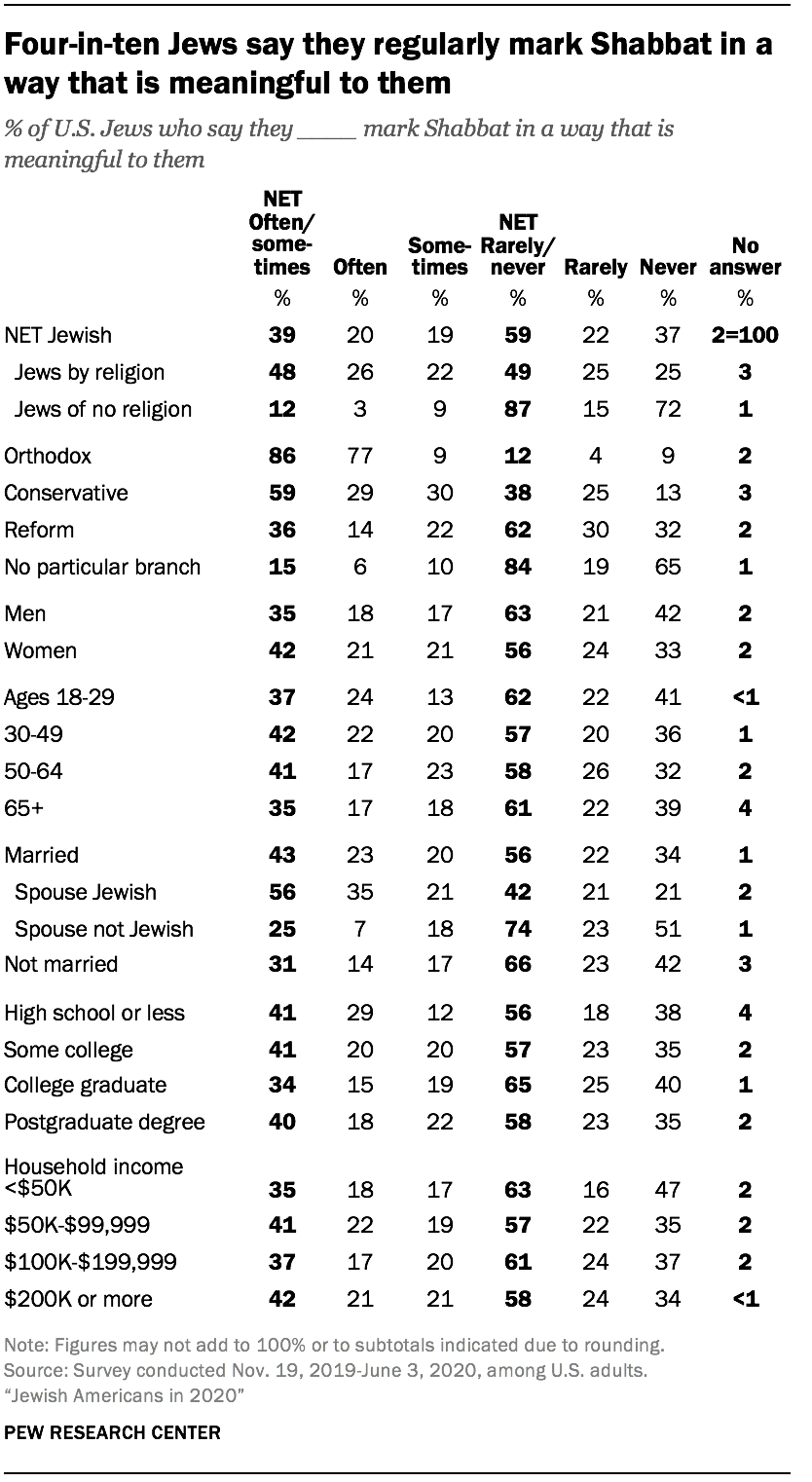

Four-in-ten U.S. Jews say they often (20%) or sometimes (19%) mark Shabbat in a way that is meaningful to them. For some this might include traditional practices like resting, attending religious services or lighting candles. For others, it might involve gathering with friends or doing community service.

As with so many other forms of participation in Jewish life, marking Shabbat in a personally meaningful way is much more common among Jews by religion than among Jews of no religion. It also is more common among in-married Jews (marriages between people of the same religion) than among those who are married to non-Jewish spouses. And it is most common among Orthodox Jews and least common among those with no denominational ties.

Most U.S. Jews connect with Judaism through food, Jewish historical sites; many others connect through Jewish media

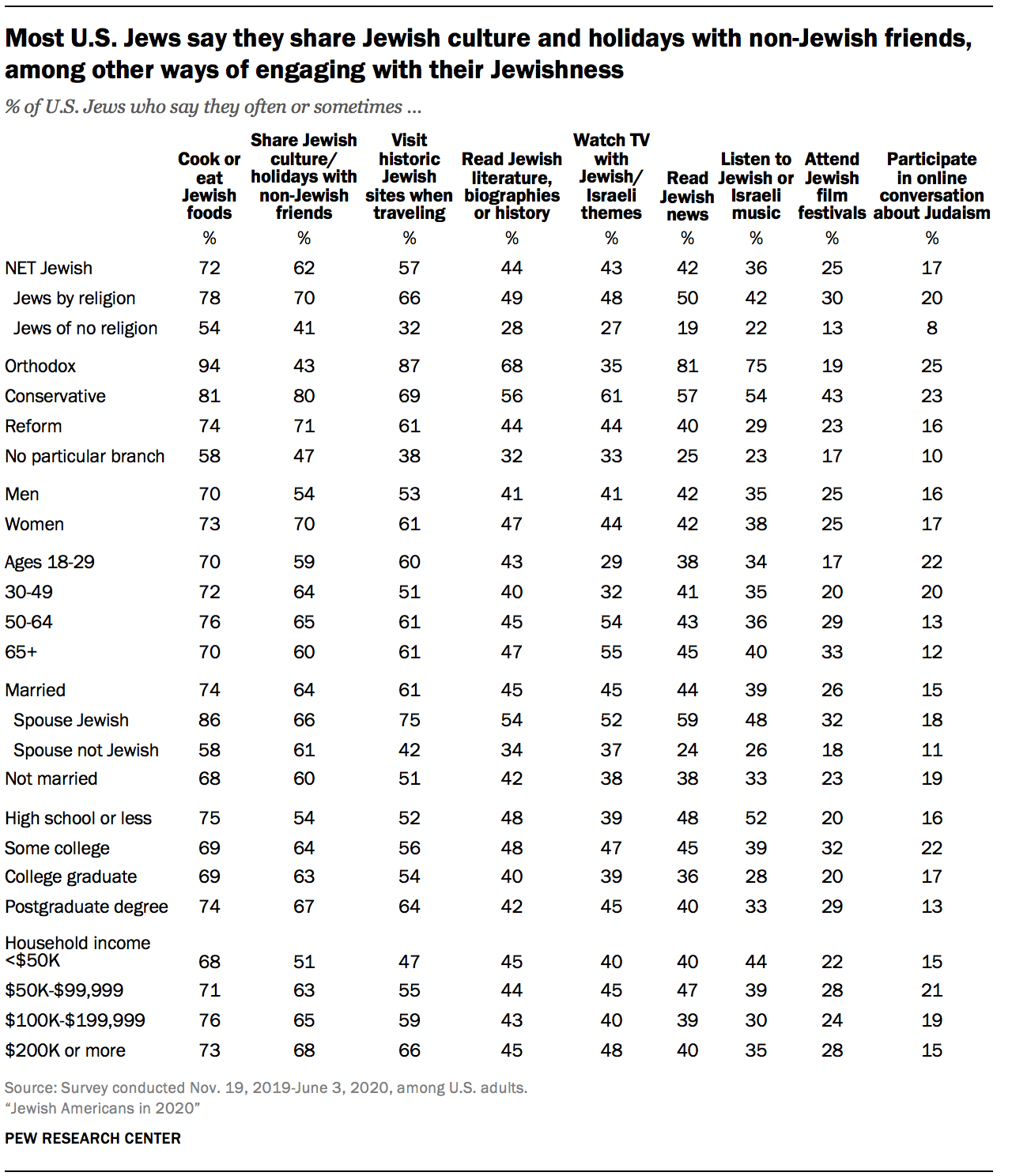

The survey included a variety of questions that asked respondents how they engage with Jewish culture. About seven-in-ten U.S. Jews say they “often” or “sometimes” cook or eat Jewish foods, making this the most common form of participation in Jewish culture asked about in the study. Six-in-ten say they at least sometimes share Jewish culture and holidays with non-Jewish friends. And most U.S. Jews (57%) also say they visit historical Jewish sites when they travel.

Smaller shares report often or sometimes reading Jewish literature, history or biographies (44%), watching television with Jewish or Israeli themes (43%), reading Jewish news in print or online (42%), or listening to Jewish or Israeli music (36%). One-quarter of U.S. Jews say they go to Jewish film festivals or seek out Jewish films at least sometimes, and 17% say they participate in online conversations about Judaism or being Jewish.

Watching television with Jewish themes and seeking out Jewish films and film festivals is more common among older Jews (ages 50 and older) than among younger Jewish adults. On the other questions, however, the differences between older and younger Jews tend to be modest.

Orthodox Jews are more likely than those who belong to other branches or streams of American Judaism to say they regularly cook or eat Jewish foods, visit Jewish historical sites, read Jewish news and literature, and listen to Jewish music. Jewish television and films, by contrast, factor much less prominently in Orthodox Jewish life; Orthodox Jews are less likely than both Conservative and Reform Jews to say they often or sometimes watch television with Jewish themes.

The survey also asked respondents to describe in their own words anything else they do that makes them feel connected with Jews and Judaism; see topline for results.

Jewish political expression

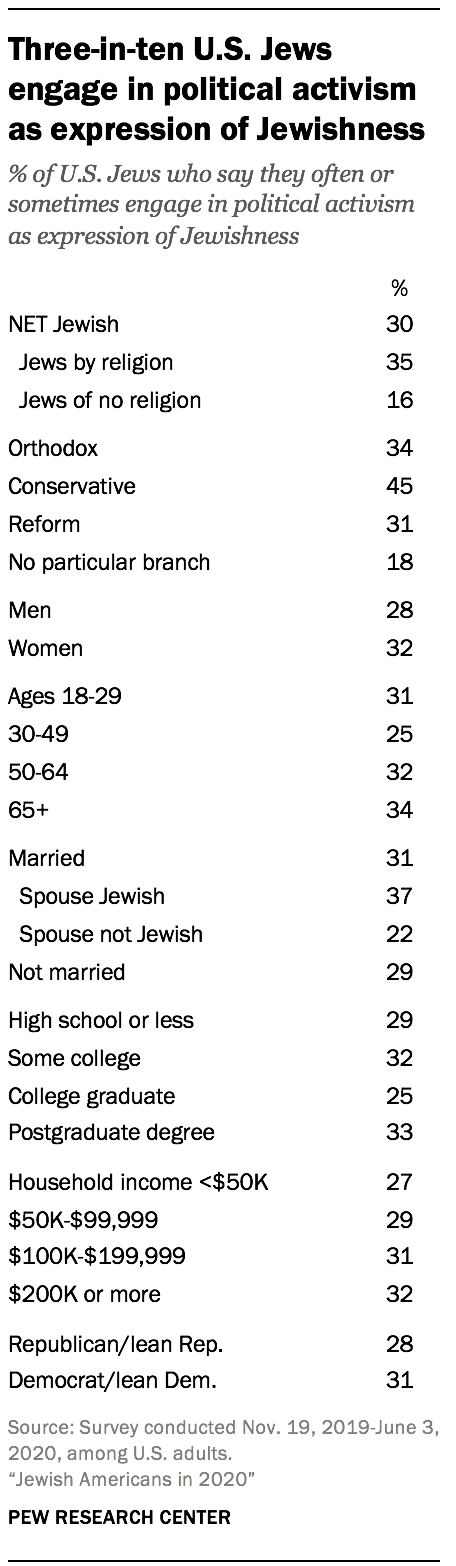

Three-in-ten Jews say they often or sometimes engage in political activism as an expression of their Jewishness. This is especially common among those who identify with Conservative Judaism (45%).

Engaging in political activism as an expression of Jewishness is about equally as common among Jews who identify with or lean toward the Republican Party (28% of whom say they at least sometimes engage in political activism as an expression of Jewishness) as it is among Jewish Democrats and those who lean Democratic (31%).

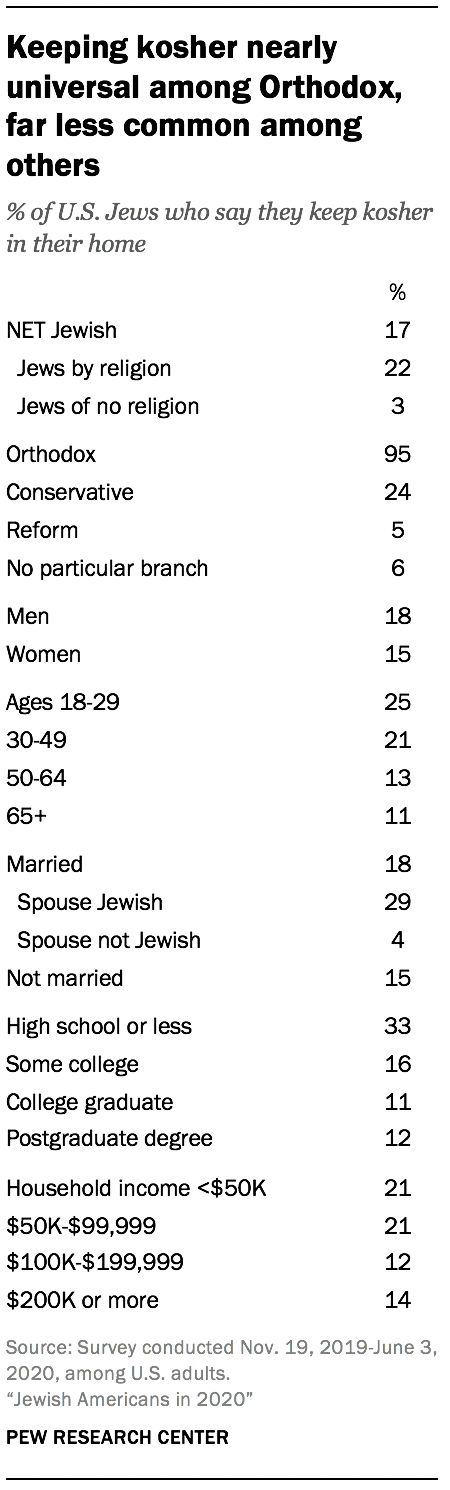

Keeping kosher

Fewer than one-in-five U.S. Jews (17%) say they keep kosher in their home, including 14% who say they separate meat and dairy and 3% who say they are vegetarian or vegan.

Keeping kosher is nearly ubiquitous in Orthodox homes: Fully 95% of Orthodox Jews in the survey say they keep kosher. About one-quarter of Conservative Jews (24%) say they keep kosher in their home. And among Reform Jews and those with no denominational association, roughly one-in-twenty say they keep kosher in their home (5% among Reform Jews, 6% among those unaffiliated with any particular branch of Judaism).

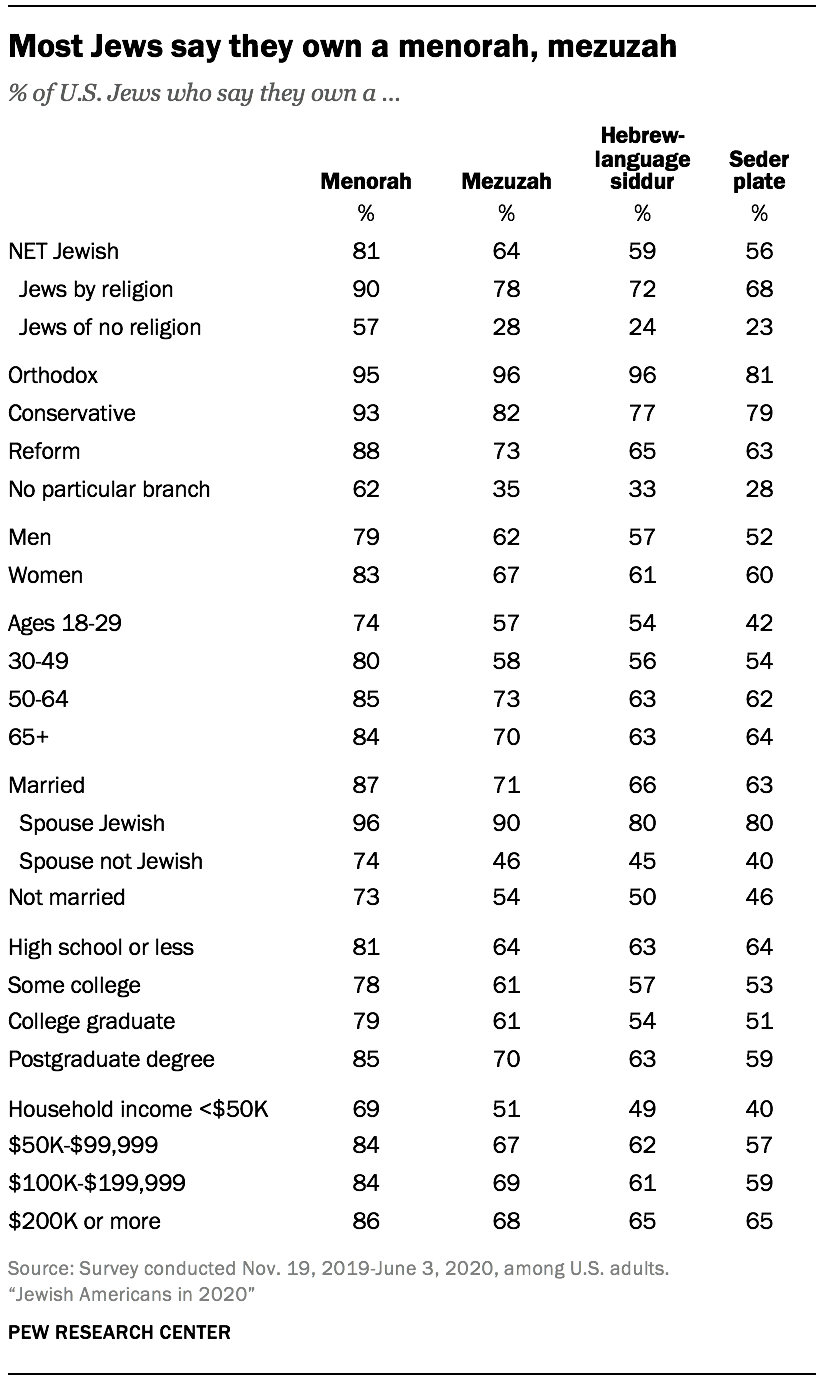

Ownership of Jewish items

Eight-in-ten U.S. Jews say they own a menorah, a candelabra used to mark the eight days of Hanukkah. Nearly two-thirds own a mezuzah, which is a parchment containing scripture passages typically affixed to the doorposts in Jewish homes. Six-in-ten U.S. Jews say they own a Hebrew-language siddur (Jewish prayer book), and 56% say they have a Seder plate designed to hold the six symbolic foods associated with the Passover meal.

Eight-in-ten U.S. Jews say they own a menorah, a candelabra used to mark the eight days of Hanukkah. Nearly two-thirds own a mezuzah, which is a parchment containing scripture passages typically affixed to the doorposts in Jewish homes. Six-in-ten U.S. Jews say they own a Hebrew-language siddur (Jewish prayer book), and 56% say they have a Seder plate designed to hold the six symbolic foods associated with the Passover meal.

Jewish people who are married to Jewish spouses are more likely than intermarried Jews to own these examples of Judaica. The same is true of those who identify with an institutional stream of Judaism (especially Orthodox Jews), compared with those who identify with no particular branch.

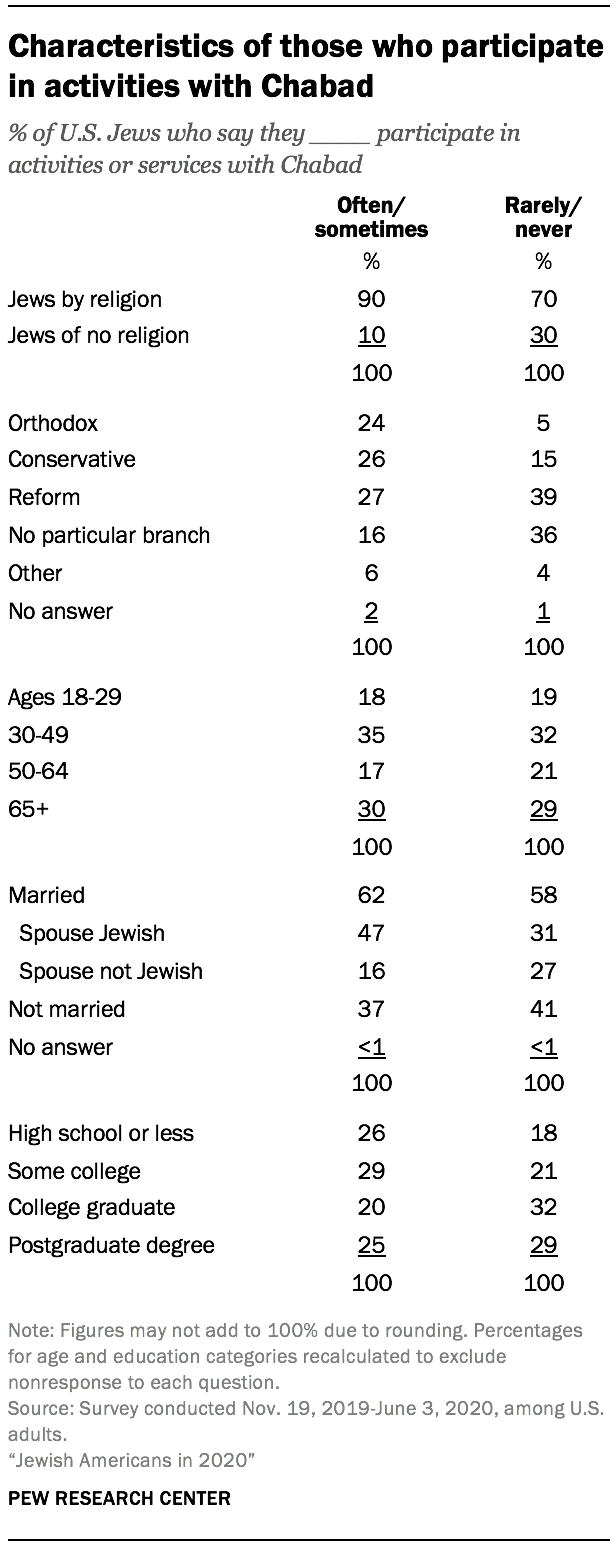

Participation in Chabad

Overall, 16% of U.S. Jewish adults say they often or sometimes participate in activities or services with Chabad, an Orthodox Jewish movement and organization that offers programs and services to Jews throughout the U.S. and the world. This includes 5% who say they “often” do this and 12% who “sometimes” participate in Chabad activities. One-in-five Jewish adults (21%) say they rarely participate in activities or services with Chabad, and 62% say they never do.

Overall, 16% of U.S. Jewish adults say they often or sometimes participate in activities or services with Chabad, an Orthodox Jewish movement and organization that offers programs and services to Jews throughout the U.S. and the world. This includes 5% who say they “often” do this and 12% who “sometimes” participate in Chabad activities. One-in-five Jewish adults (21%) say they rarely participate in activities or services with Chabad, and 62% say they never do.

What are the characteristics of those who regularly engage with Chabad? The vast majority identify as Jewish by religion (90%) as opposed to Jews of no religion (10%). The age structure of those who participate with Chabad is very similar to the age structure of those who do not. Chabad participants are more likely than other Jews to have a Jewish spouse, and they have lower levels of education, on average, than Jews who do not participate in Chabad activities.

One-quarter of Chabad participants are Orthodox Jews (24%), and another quarter identify with Conservative Judaism (26%) – both much higher than the shares of Orthodox (5%) and Conservative (15%) Jews among those who rarely or never take part in Chabad events. But about half of Chabad participants are from other streams or don’t affiliate with any particular branch of Judaism, perhaps reflecting Chabad’s outreach toward less observant Jews.

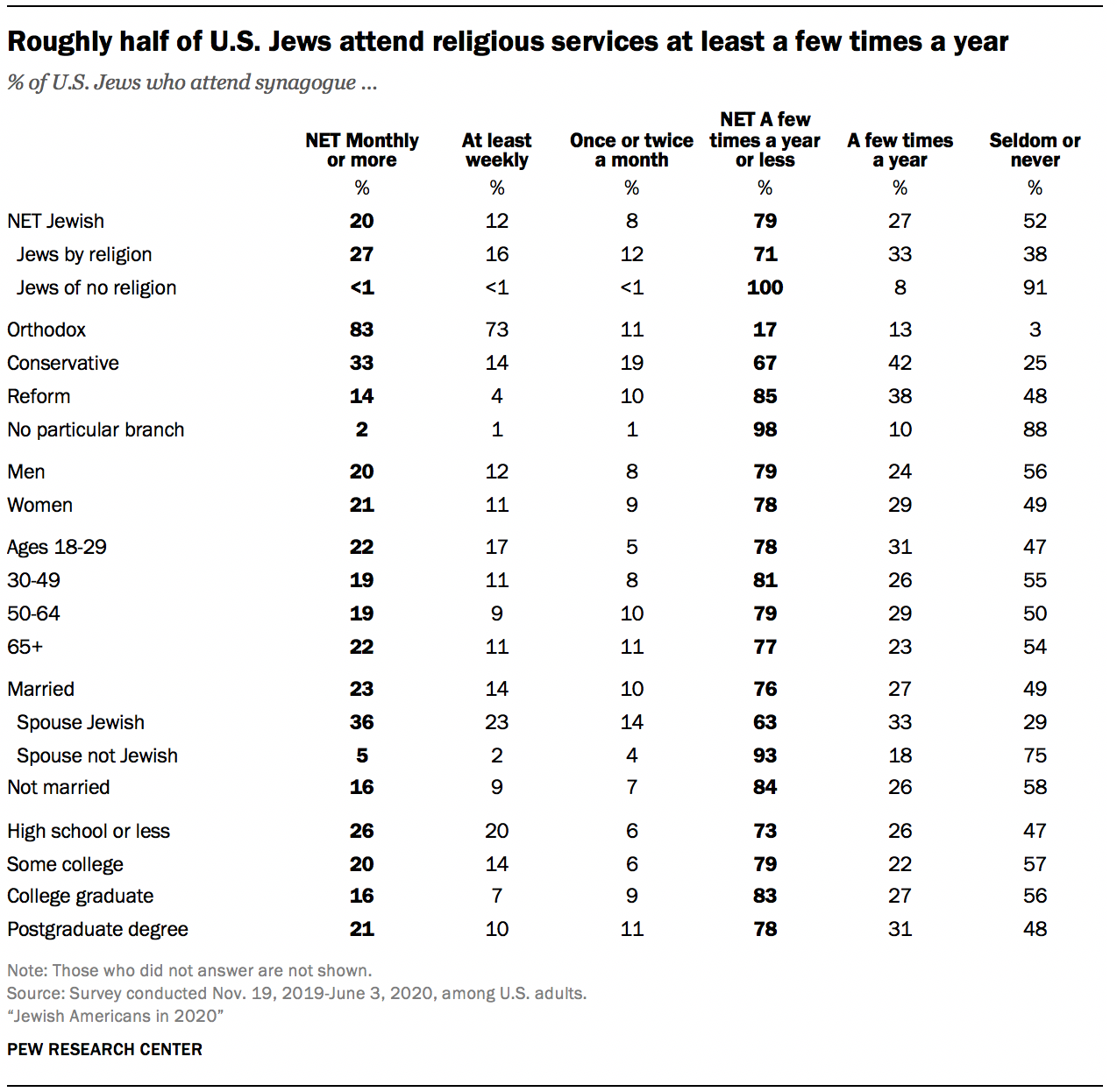

Synagogue attendance and membership

One-in-five U.S. Jews say they attend services at a synagogue, temple, minyan or havurah at least once or twice a month, including 12% who go weekly or more often. One-quarter (27%) say they attend a few times a year, such as for High Holidays. And half of U.S. Jews (including roughly nine-in-ten Jews of no religion) say they seldom or never attend Jewish religious services.

Monthly attendance at Jewish religious services is equally common among Jewish men (20%) and women (21%), and roughly equivalent among younger Jews and older Jews. Those who are married to a Jewish spouse attend Jewish religious services at much higher rates (36% at least monthly) compared with those who are married to a non-Jewish spouse (5%) or who are not married (16%).

Eight-in-ten Orthodox Jews say they attend Jewish religious services at least once or twice a month, including 73% who do so at least once a week. Worship attendance is less common among Conservative and Reform Jews, though most Conservative Jews and about half of Reform Jews attend at least a few times a year. Among Jews who have no particular denominational affiliation, about nine-in-ten (88%) seldom or never attend Jewish religious services.

Jewish Americans are less likely than U.S. adults overall to attend religious services regularly. One-in-five Jews say they attend a synagogue at least once per month, compared with about one-third of U.S. adults who say they attend religious services as often. However, Jews are more likely to say they go to religious services a few times a year (such as for High Holidays) than Americans overall (27% vs. 15%). Half of Jewish adults say they seldom or never go to synagogue, similar to the share of adults in the overall public who say they seldom (24%) or never (26%) go to church or other religious services.

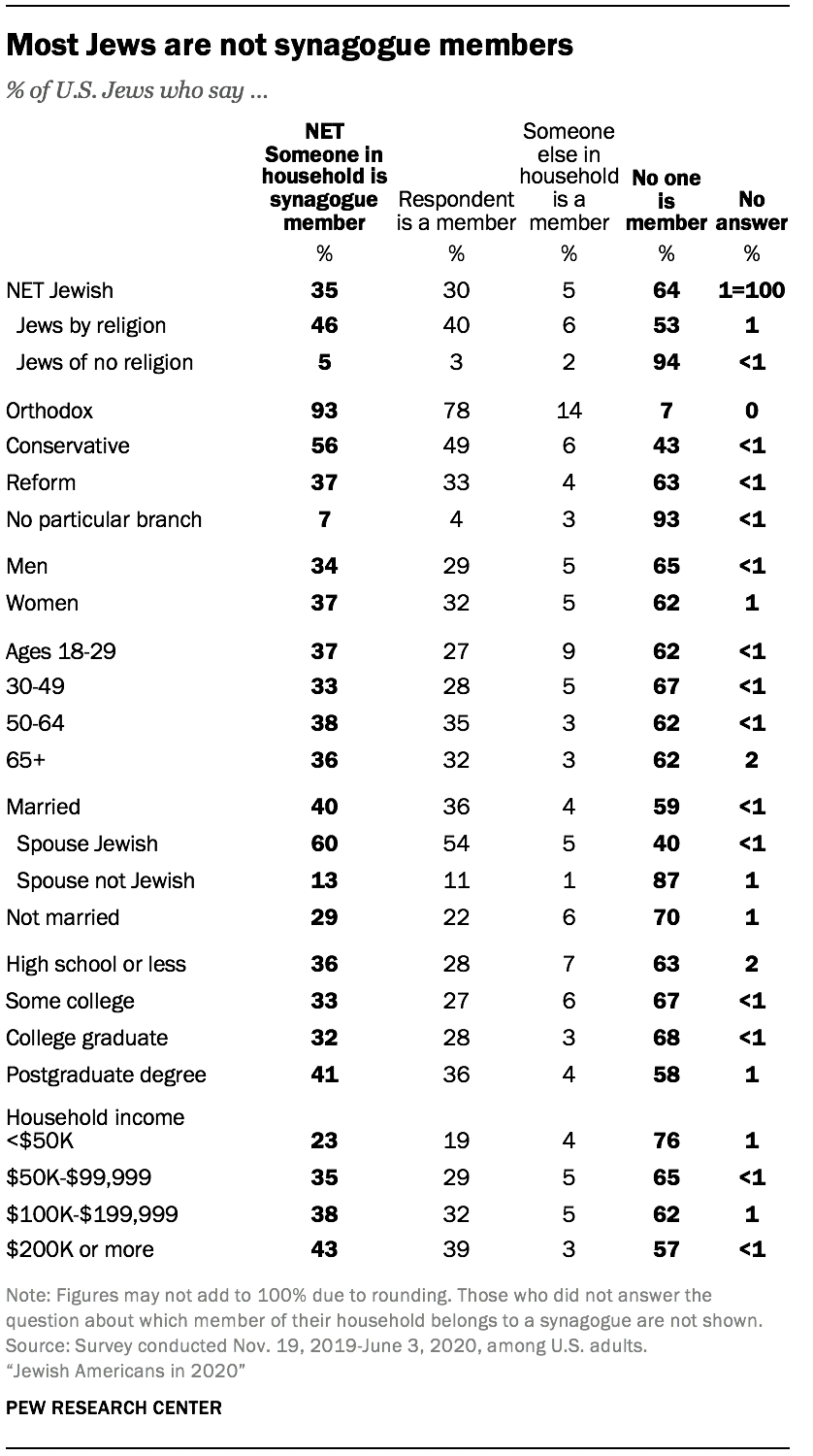

About one-third of U.S. Jews (35%) say they live in a household where someone is a formal member of a synagogue. This includes 46% of Jews by religion, compared with 5% of Jews of no religion.

About one-third of U.S. Jews (35%) say they live in a household where someone is a formal member of a synagogue. This includes 46% of Jews by religion, compared with 5% of Jews of no religion.

Roughly nine-in-ten Orthodox Jewish respondents (93%) live in households where someone is a member of a synagogue, as do 56% of those associated with the Conservative movement. Fewer Reform Jews (37%) say they or someone else in their household belongs to a synagogue, and just 7% of Jews with no denominational affiliation say this.

Synagogue membership peaks at 43% among Jews in households with annual incomes of $200,000 or more. By contrast, one-quarter of Jews whose family income is less than $50,000 say that someone in the household is a synagogue member. Among U.S. Jews who attend synagogue a few times a year or less, 17% say cost is a reason they do not attend more often.

Because Pew Research Center’s 2013 survey was conducted by phone and the 2020 survey was conducted by mail and online, the results on synagogue attendance and membership are not directly comparable. A 2020 experiment (see Appendix B) indicates that Jewish Americans, like U.S. adults in general, tend to report higher levels of attendance at religious services when speaking with a live interviewer on the phone than they do when writing their answers in private. (Social scientists attribute this primarily to “social desirability” bias, the often unconscious desire to give answers that other people will like or expect.) In the case of synagogue attendance and membership, this means that any apparent change from 2013 to 2020 may be attributable to methodological differences between the two surveys rather than to real changes in behavior.

Among those who rarely or never attend synagogue, what keeps them away?

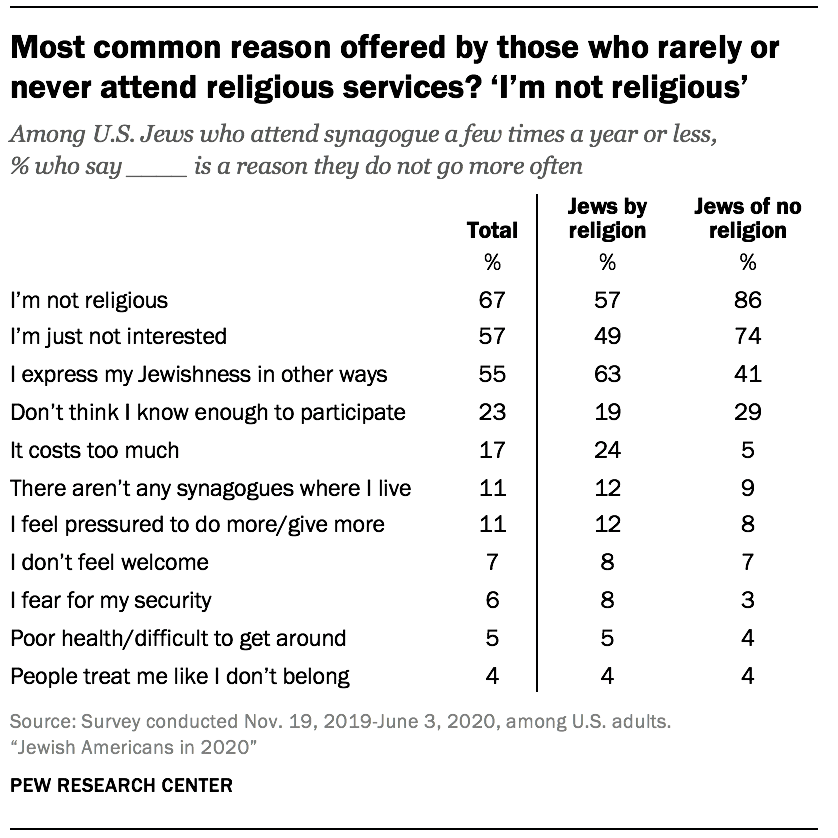

The survey asked Jews who attend religious services a few times a year or less (including those who never attend) whether each of a number of possible factors is a reason why they do not go more often. Respondents could select multiple reasons, indicating all that apply to them. The most common answer was “I’m not religious,” which two-thirds (including 86% of Jews of no religion) cite as a reason they do not regularly attend Jewish religious services. More than half say they are “just not interested” or that they express their Jewishness in other ways.

The survey asked Jews who attend religious services a few times a year or less (including those who never attend) whether each of a number of possible factors is a reason why they do not go more often. Respondents could select multiple reasons, indicating all that apply to them. The most common answer was “I’m not religious,” which two-thirds (including 86% of Jews of no religion) cite as a reason they do not regularly attend Jewish religious services. More than half say they are “just not interested” or that they express their Jewishness in other ways.

Roughly one-quarter of U.S. Jews (23%) say they do not attend services regularly because they do not know enough to participate, and 17% cite cost as a factor that keeps them away. And one-in-ten say they do not attend synagogue regularly either because they don’t feel welcome (7%) or because people treat them like they don’t belong (4%). Roughly one-in-ten or fewer say there are no nearby congregations for them to attend, that when they go they feel pressured to do more or donate more than they are comfortable with, that they fear for their security at synagogue, or that their poor health or limited mobility makes it difficult for them to attend.

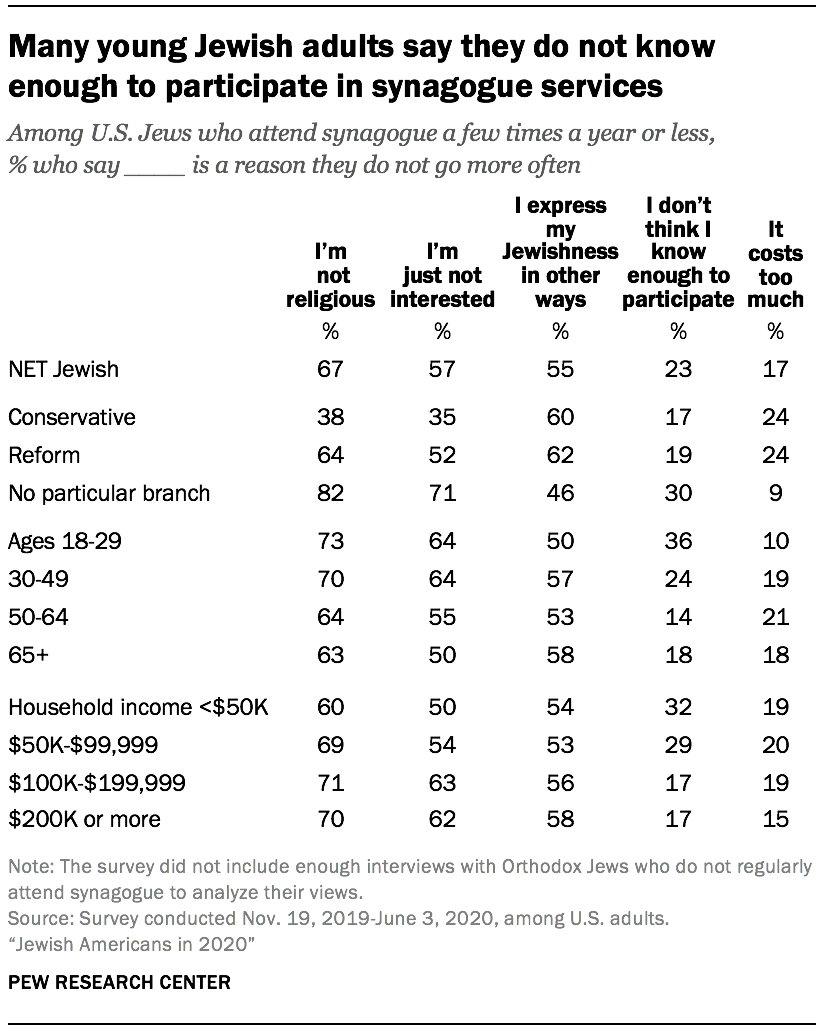

Younger Jews are more likely than their elders to say that a lack of knowledge about how to participate keeps them away from Jewish religious services. Jews under age 50 also are significantly more apt than those who are older to say they are “just not interested” in attending religious services. At the same time, Jews under age 30 are less likely than older Jews to cite cost as a factor keeping them away from religious services.

Younger Jews are more likely than their elders to say that a lack of knowledge about how to participate keeps them away from Jewish religious services. Jews under age 50 also are significantly more apt than those who are older to say they are “just not interested” in attending religious services. At the same time, Jews under age 30 are less likely than older Jews to cite cost as a factor keeping them away from religious services.

Compared with Conservative and Reform Jews who do not attend religious services regularly, those who don’t affiliate with any particular branch or stream of U.S. Judaism are more inclined to cite lack of religiousness and lack of interest as factors. By contrast, Conservative and Reform Jews who attend infrequently are more likely than those with no denominational affiliation to say they express their Jewishness in other ways and to cite cost as an explanation for why they do not attend religious services.

Roughly one-in-five Jews with family incomes of less than $50,000 cite cost as a reason they do not attend religious services more often, which is not significantly different than the 15% of Jews with household incomes above $200,000 who say this.

Some Jewish community leaders have wondered whether intermarried Jews, Jews of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, and Jews who have family members from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds might avoid synagogues because they do not feel welcome. The survey finds that 8% of intermarried Jews who rarely or never attend religious services say it is because they don’t feel welcome, virtually identical to the 7% of in-married Jews who say this. But Jews who live in households with at least one non-White person (including possibly the respondent) are somewhat more likely than Jews in households where everyone is White to cite an unwelcoming atmosphere as a reason for not attending religious services (11% vs. 6%). The survey did not include enough interviews with Jewish adults who identify as Hispanic, Black, Asian, some other race or multiracial to reliably report their views, either as separate racial/ethnic groups or even in aggregate (as all non-White respondents combined).

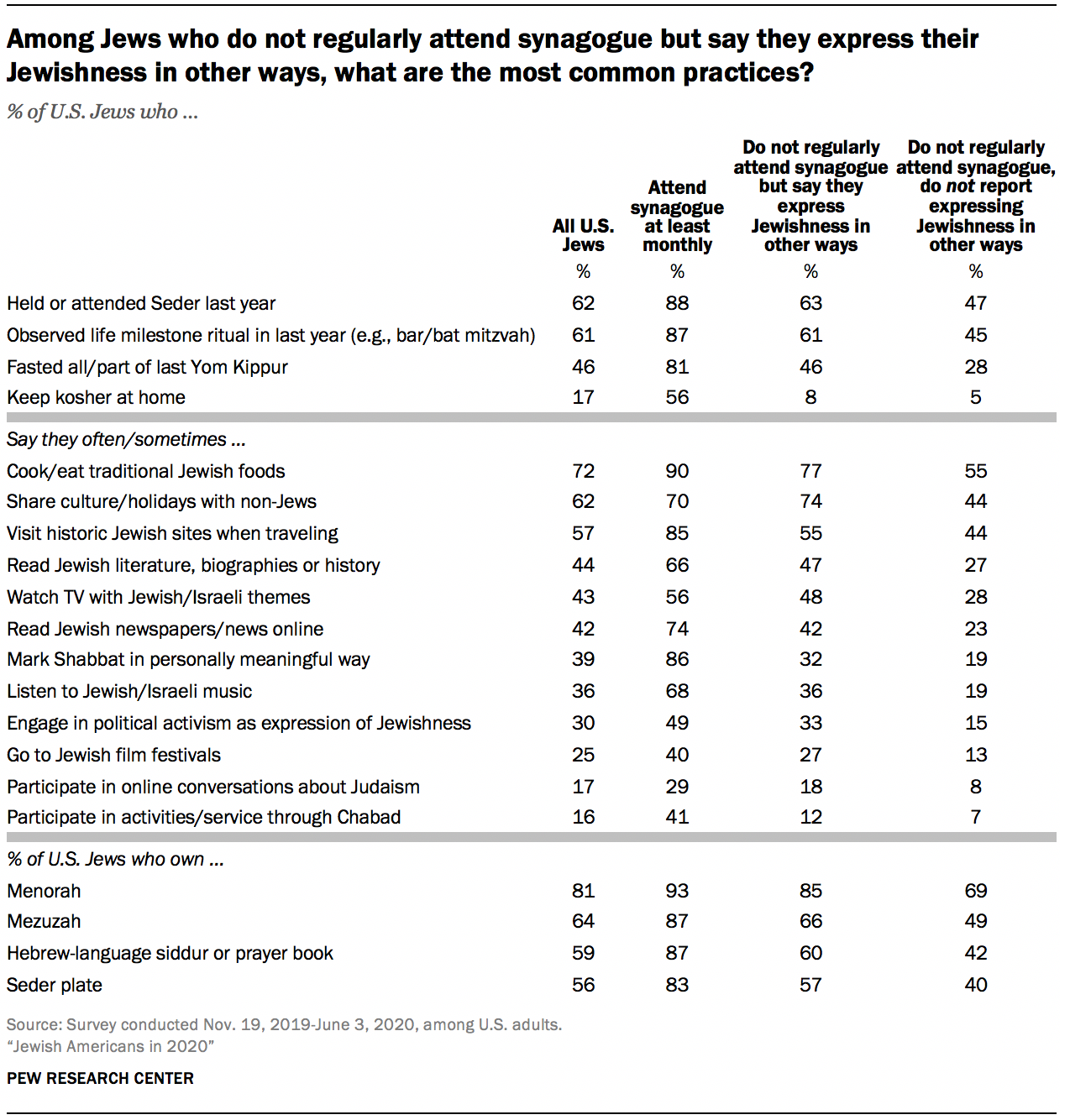

A closer look at those who do not attend synagogue regularly but say they express their Jewishness in other ways

More than half of U.S. Jews who attend religious services a few times a year or less often say that one of the reasons they do not go more is that they “express their Jewishness in other ways,” making this one of the most commonly cited reasons for not attending religious services. This raises the question: How – if at all – does this group express Jewishness in other ways?

The survey finds that, among Jews who attend a few times a year or less, those who give this response are more engaged in Jewish life on a variety of measures than those who do not say it’s because they express their Jewishness in other ways. For example, 74% of non-attenders who say they express their Jewishness in other ways report often or sometimes sharing Jewish culture and holidays with non-Jewish friends, and 63% held or attended a Seder last year. By contrast, among non-attenders who do not give this explanation for why they do not go to religious services, the comparable figures are 44% and 47%, respectively.

The survey also shows, however, that non-attenders who say they do not go to religious services because they express their Jewishness in other ways are consistently less engaged in Jewish life than are Jews who do attend religious services at least once or twice a month.

Among regular synagogue attenders, what motivates them to attend?

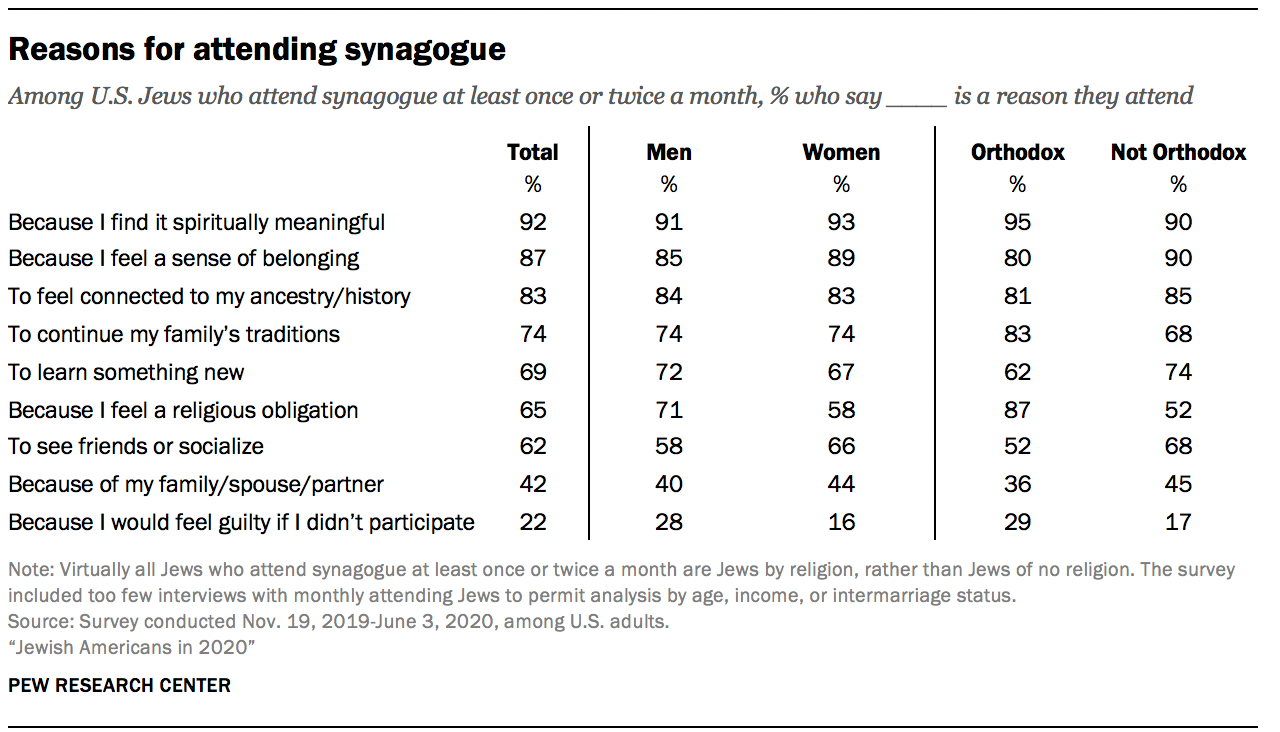

The survey also asked the 20% of U.S. Jews who do attend religious services at least once or twice a month about their reasons for doing so. Within this group, fully 92% say they do so because they find it spiritually meaningful, while 87% point to the sense of belonging they derive and 83% cite a connection to their ancestry and history. Smaller majorities say continuing their family’s traditions (74%), learning something new (69%), feeling a sense of religious obligation (65%) or socializing (62%) are factors in why they attend regularly.

Fewer than half say they attend primarily because of their family, spouse or partner (42%) or because they would feel guilty if they didn’t (22%).

Jewish men are more likely than women to say they attend religious services regularly out of a sense of obligation, while Jewish women are a bit more likely than men to say they go to see friends and socialize. Orthodox Jews are more apt than other Jews to cite continuing family traditions and a sense of obligation as reasons for their frequent religious attendance. By contrast, non-Orthodox Jews more commonly cite the knowledge they gain and the opportunity to socialize as reasons they regularly attend religious services.

Jewish men are more likely than women to say they attend religious services regularly out of a sense of obligation, while Jewish women are a bit more likely than men to say they go to see friends and socialize. Orthodox Jews are more apt than other Jews to cite continuing family traditions and a sense of obligation as reasons for their frequent religious attendance. By contrast, non-Orthodox Jews more commonly cite the knowledge they gain and the opportunity to socialize as reasons they regularly attend religious services.

Sidebar: Most U.S. Jews don’t go to synagogue, so rabbis and a host of new organizations are trying to innovate

Even before COVID-19 led synagogues to shut their sanctuaries, non-Orthodox Jews in America hadn’t been flocking to weekly Shabbat services. Most go to services just a few times a year at most, and fewer than half are members of a synagogue, according to Pew Research Center’s 2020 survey of American Jews, conducted mostly prior to the coronavirus outbreak. To provide another window into some of the changes occurring in American Jewish life, Pew Research Center conducted a series of in-depth interviews with rabbis and other Jewish leaders. These conversations were separate from the survey of U.S. Jews. Although the interviewees were not selected in a scientific manner, and hence are not representative of Jewish leaders overall, we sought a diversity of viewpoints and have tried to convey them impartially, without taking sides or promoting any positions, policies or outcomes.

To provide another window into some of the changes occurring in American Jewish life, Pew Research Center conducted a series of in-depth interviews with rabbis and other Jewish leaders. These conversations were separate from the survey of U.S. Jews. Although the interviewees were not selected in a scientific manner, and hence are not representative of Jewish leaders overall, we sought a diversity of viewpoints and have tried to convey them impartially, without taking sides or promoting any positions, policies or outcomes.

In a series of in-depth interviews separate from the survey itself, nearly three dozen rabbis and Jewish community leaders described their efforts to increase engagement in Jewish life. Many have concluded that, in the 21st century, they cannot assume Jewish families will join a synagogue – or be active in one – out of obligation. Instead, they think synagogues and other Jewish organizations need to come up with new and unconventional ways to engage with Jews who don’t go to religious services, can’t read Hebrew and have varying levels of Jewish education.

“People today are looking to Jewish institutions to satisfy them where they are,” said Rabbi Howard Stecker of Temple Israel in Great Neck, a Conservative synagogue in Long Island, New York. “People are looking to find something that’s meaningful in their lives. If a synagogue can provide it – is nimble enough – then people will respond to the extent that their needs are being satisfied. But the idea that you support a synagogue just because that’s the right thing to do … seems to be fading over time in the 20-plus years that I’ve been a rabbi.”

The 2013 Pew Research Center survey pointed to the growth of “Jews of no religion,” particularly among young Jewish adults – an echo, in Jewish life, of the rise of the “nones” in American religious life more broadly. The 2020 study finds that among Jews who go to synagogue no more than a few times a year, roughly half (55%) say they have “other ways” of expressing their Jewishness. Many cite multiple, overlapping reasons for not going to a synagogue: Two-thirds say they aren’t religious, 57% say they are “just not interested” in religious services, and nearly a quarter (23%) say they “don’t know enough” to participate.

Many of the rabbis interviewed are attempting various experiments – some rather modest, others more ambitious – designed to make Jews more comfortable in religious settings. For example, Rabbi Ron Fish of Temple Israel in Sharon, Massachusetts, said that for Jews disinclined to attend traditional services, his synagogue has a monthly Shabbat service that includes drumming and meditation. And, on the second day of Rosh Hashanah each year, it has offered an outdoor service – “Rosh Hashanah in the Woods,” billed as “a Rosh Hashanah experience where we can be ourselves, pray differently, relate to God, and reach within to access a spiritual dimension not always attainable in a sanctuary.”

Another approach is to lead religious discussions at a local bar, often under a cheeky moniker such as “Torah on Tap.” “I meet them in their environment,” said Rabbi Mark Mallach, rabbi emeritus of Temple Beth Ahm Yisrael in Springfield, New Jersey. “I pay for the first round. I try to come up with discussion topics relevant to them.”

Besides synagogues, many other organizations are trying to draw in young Jewish adults, families with children, intermarried couples, and other hard-to-reach segments of the population. The list of new organizations is long, as major donors to Jewish causes increasingly are funding nonprofits that foster engagement with Jewish life in specific ways. In “Giving Jewish: How Big Funders Have Transformed American Jewish Philanthropy,” Jack Wertheimer, professor of American Jewish History at the Jewish Theological Seminary, describes a decades-long shift in patterns of charitable giving. Whereas in the mid-to-late 20th century big donors tended to give to umbrella organizations such as Jewish Federations and UJA (United Jewish Appeal) campaigns and to causes such as supporting Israeli institutions, Wertheimer writes, the more recent trend, starting in the 1990s, has been to fund specific initiatives to increase Jewish engagement (i.e., “activities that bring the least involved Jews to episodic gatherings of a Jewish flavor”) and to build Jewish identity. He estimates that the top 250 Jewish foundations together give grants totaling $900 million to $1 billion per year for Jewish purposes.

Some of these “spiritual startups” have benefitted from seed capital and training provided by incubator organizations like UpStart, which distributes roughly $1.5 million a year in grants, according to Aaron Katler, UpStart’s chief executive officer.

Among the nonprofits that have grown rapidly in recent years: Moishe House, founded in Oakland, California, in 2006, helps Jews in their 20s form strong communities. Limmud, founded in the UK in the 1980s, expanded internationally in 1999 and now organizes festivals, workshops and other events fostering Jewish learning around the world. PJ Library began free distribution of Jewish children’s books in 2005 and now distributes works by authors and illustrators in multiple languages in more than 30 countries. The Jewish Emergent Network was founded in 2014 by rabbis of seven unaffiliated communities (including IKAR in Los Angeles and Sixth & I in Washington) to share ideas and build on their respective successes in “attracting unaffiliated and disengaged Jews to a rich and meaningful Jewish practice.” And Hazon, a newly reinvigorated nonprofit that traces its roots back to the Jewish Working Girls Vacation Society in 1893, fosters environmental sustainability.

Another recent example is OneTable, which brings together Jews in their 20s and 30s for Shabbat dinners at people’s homes. Anyone in that age range (except for college students) can apply on OneTable’s website to host Shabbat dinners or can select among a list of Shabbat dinners being hosted in their area. OneTable, with financial support from Jewish foundations, subsidizes each dinner with $10 per attendee, up to $100.

In 2019, OneTable funded around 9,000 Shabbat meals in more than 400 cities across the United States, with a total of 109,000 people participating (including repeaters), said Aliza Kline, its chief executive officer. In her view, the numbers prove that young American Jews are open to religious experiences outside of synagogue settings. “This generation is less engaged institutionally than other generations, but that doesn’t mean they’re not spiritually connected. … This is a DIY ritual by design, and that really fits with how people are connecting with their culture, their traditions,” Kline said.

Yet alongside these – and many other – growing organizations, there are plenty of Jewish spiritual startups that have failed to catch on, as well as older organizations that have been losing ground, like the once-flourishing NJOP (National Jewish Outreach Program), which for more than 30 years has funded programs to teach Jews to read Hebrew and to celebrate Shabbat at a synagogue. More than 250,000 Jews have studied Hebrew through the program, and more than 1 million have attended its “Shabbat Across America and Canada” program, said Rabbi Ephraim Buchwald, NJOP’s director.

But attendance has declined dramatically at both of these synagogue-based programs over the last 15 years, Buchwald said. Even before the pandemic, enrollment in the Hebrew programs had dropped to around 4,000 a year from 10,000, and Shabbat Across America and Canada drew around 20,000 annually, down from 80,000. “People just stopped responding, so the numbers of people that we’ve been teaching has dropped precipitously … I think because the young people are not interested in these types of programs,” Buchwald said. “They’re not interested in coming to a synagogue.”

Some rabbis said the American Jewish community seems less cohesive now than just a few decades ago, when the memory of the Holocaust was more fresh, Israel was widely viewed as an underdog in its conflict with surrounding Arab states, and support for Soviet Jews galvanized Jewish communities. Paradoxically, Jewish religious institutions may also be a victim of the success Jews have had in integrating into American society: There has been a blurring of the lines between Jewish and non-Jewish identity, and Jews are less likely to depend on synagogues for their social circles than was the case decades ago, according to the rabbis.

“In the past, membership was more of a given,” said Rabbi Angela Buchdahl of Central Synagogue in New York City. “People felt they had to join a synagogue in order to belong and affiliate. Now I would say, there’s a lot more ‘do-it-yourself Judaism’ and internet Judaism and virtual Judaism.”

The price of membership, often a few thousand dollars a year, also can keep people from joining a synagogue, the rabbis said. In recent years, a small number of synagogues have done away with traditional dues structures, hoping to remove a barrier to membership. As of 2017, more than 60 synagogues across the country had eliminated mandatory dues, according to a national study conducted by the UJA Federation of New York. The study noted that these synagogues generally say their decisions led to membership increases, but that financial contributions per household also tend to be lower than before.

Rabbi Jay Siegel of Congregation Beth Shalom in Santa Clarita, California, said the voluntary dues structure instituted there in 2014 helped attract and retain members. “It created a very low barrier for membership, which was great because you had people who could participate that, under the classic dues structure, it might have been prohibitive. … And it removed some of the uncomfortable conversations. People hated being asked for money.”

One Jewish place of worship that never had a traditional, dues-based membership structure is Sixth & I, a synagogue and cultural center in Washington, D.C. Its senior rabbi, Shira Stutman, said Sixth & I caters mainly to people in their 20s and 30s, a group that she feels has been underserved by traditional synagogues, which tend to be family-centered. For its budget, the synagogue relies on a group of major donors, institutional funders and more than 3,000 individuals who give money at least annually. In addition, it asks visitors to pay to attend its arts and cultural events, social activities, religious classes, and meals after Shabbat services. In a typical year prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the synagogue drew about 80,000 paying visitors; in 2020, it shifted to mostly online events, which brought in similar numbers of participants but lower revenues, she said.

“People will pay for things that they think are meaningful to them if you give them something quality,” Stutman said. “Many of these kids are spending $18 on one cocktail in a bar. If they can spend $18 on a cocktail, they can spend $18 for a class.”

A much different approach to engagement is taken by Chabad-Lubavitch, a Brooklyn-based organization with Hasidic origins in Russia and Poland that sends emissaries (“shlichim”) to the far corners of the globe and attracts many non-Orthodox Jews even though its leaders are Haredi (ultra-Orthodox). Chabad synagogues don’t have membership dues. Instead, they seek donations from Jews who go to their adult-education classes, attend their services and holiday celebrations, and have Shabbat dinners at their rabbis’ homes, which sometimes may double as synagogues, said Rabbi Motti Seligson, a spokesman for Chabad-Lubavitch.

Overall, 16% of American Jews say they participate in Chabad activities or services either “often” (5%) or “sometimes” (12%), according to the 2020 survey. About half of those participants identify as Reform or Conservative Jews. Seligson said Chabad’s approach allows Jews to form meaningful personal connections with rabbis more easily than is generally the case at larger synagogues.

“You may first meet the rabbi for coffee and start a weekly class, and maybe you’ll be over with your family for a Shabbat diner at the rabbi’s home a number of times,” he said. “That may all be before you begin attending synagogue. … You may not even feel comfortable going to ‘the synagogue part’ of this community, but you’ll still be part of the community and still be embraced.”

Next: 4. Marriage, families and children

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition