According to Mouood, quoting by nsarchive:

Iraq and Weapons of Mass Destruction

Between Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, and the commencement of military action in January 1991, then President George H.W. Bush raised the specter of the Iraqi pursuit of nuclear weapons as one justification for taking decisive action against Iraq. In the then-classified National Security Directive 54, signed on January 15, 1991, authorizing the use of force to expel Iraq from Kuwait, he identified Iraqi use of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) against allied forces as an action that would lead the U.S. to seek the removal of Saddam Hussein from power.

In the aftermath of Iraq’s defeat, the U.S.-led U.N. coalition was able to compel Iraq to agree to an inspection and monitoring regime, intended to insure that Iraq dismantled its WMD programs and did not take actions to reconstitute them. The means of implementing the relevant U.N. resolutions was the Special Commission on Iraq (UNSCOM). That inspection regime continued until December 16, 1998 – although it involved interruptions, confrontations, and Iraqi attempts at denial and deception – when UNSCOM withdrew from Iraq in the face of Iraqi refusal to cooperate, and harassment.

Subsequent to George W. Bush’s assumption of the presidency in January 2001, the U.S. made it clear that it would not accept what had become the status quo with respect to Iraq – a country ruled by Saddam Hussein and free to attempt to reconstitute its assorted weapons of mass destruction programs. As part of their campaign against the status quo, which included the clear threat of the eventual use of military force against the Iraqi regime, the U.S. and Britain published documents and provided briefings detailing their conclusions concerning Iraq’s WMD programs and its attempts to deceive other nations about those programs.

As a result of the U.S. and British campaign, and after prolonged negotiations between the United States, Britain, France, Russia and other U.N. Security Council members, the United Nations declared that Iraq would have to accept even more intrusive inspections than under the previous inspection regime – to be carried out by the U.N. Monitoring, Verification, and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) – or face “serious consequences.” Iraq agreed to accept the U.N. decision and inspections resumed in late November 2002. On December 7, 2002, Iraq submitted its 12,000 page declaration, which claimed that it had no current WMD programs. Intelligence analysts from the United States and other nations immediately began to scrutinize the document, and senior U.S. officials quickly rejected the claims.

Over the next several months, inspections continued in Iraq, and the chief inspectors, Hans Blix (UNMOVIC) and Mohammed El Baradei (IAEA) provided periodic updates to the U.N. Security Council concerning the extent of Iraqi cooperation, what they had or had not discovered, and what they believed remained to be done. During that period the Bush administration, as well as the Tony Blair administration in the United Kingdom, charged that Iraq was not living up to the requirement that it fully disclose its WMD activities, and declared that if it continued along that path, “serious consequences” – that is, invasion – should follow.

The trigger for military action preferred by the British government, other allies, and at least some segments of the Bush administration, was a second U.N. resolution that would authorize an armed response. Other key U.N. Security Council members – including France, Germany, and Russia – argued that the inspections were working and that the inspectors should be allowed to continue. When it became apparent that the Council would not approve a second resolution, the United States and Britain terminated their attempts to obtain it. Instead, they, along with other allies, launched Operation Iraqi Freedom on March 19, 2003 – a military campaign that quickly brought about the end of Saddam Hussein’s regime and ultimately resulted in his capture.

As U.S. forces moved through Iraq, there were initial reports that chemical or biological weapons might have been uncovered, but closer examinations produced negative results. In May 2003, the Bush administration decided to establish a specialized group of about 1,500 individuals, the Iraq Survey Group (ISG), to search the country for WMD – replacing the 75th Exploitation Task Force, which had originally been assigned the mission. Appointed to lead the Group, whose motto is “find, exploit, eliminate,” was Maj. Gen. Keith Dayton, the head of the Defense Intelligence Agency’s Directorate of Operations. In June, David Kay, who served as a U.N. weapons inspector after Operation Desert Storm, was appointed special advisor and traveled to Iraq to lead the search.

By the time of the creation of the ISG, and continuing to the date of this publication, a controversy has existed over the performance of U.S. (and British) intelligence in collecting and evaluating information about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction programs. The reliability of sources has been questioned. It has been suggested that some human intelligence may have been purposeful deception by the Iraqi intelligence and security services, while exiles and defectors may have provided other intelligence seeking to influence U.S. policy.

The quality of the United Kingdomanalysis has also come under scrutiny. The failure to find weapons stocks or active production lines, undermining claims by the October 2002 NIE and both President Bush and Secretary of State Colin Powell, has been one particular cause for criticism. Controversy has also centered around specific judgments – in the United States with regard to assessments of Iraq’s motives for seeking high-strength aluminum tubes, and in the United Kingdom with respect to the government’s claim that Iraq sought to acquire uranium from Africa. Post-war evaluation of captured material, particularly two mobile facilities that the CIA and DIA judged to be biological weapons laboratories, has also been the subject of dispute.

In addition, members of Congress and Parliament, as well as potential political opponents and outside observers have criticized the use of intelligence by the Bush and Blair administrations. Charges have included outright distortion, selective use of intelligence, and exertion of political pressure to influence the content of intelligence estimates in order to provide support to the decision to go to war with Iraq.

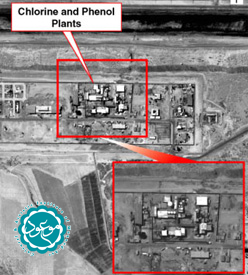

The material presented in this electronic briefing book includes both essential pre-war documentation and documents produced or released subsequent to the start of military action in March 2003. Pre-war documentation includes the major unclassified U.S. and British assessments of Iraq’s WMD programs; the IAEA and UNSCOM reports covering the final period prior to their 1998 departure, and between November 27, 2002, and February 2003; the transcript of a key speech by President Bush; a statement of U.S. policy toward combating WMD; the transcript of and slides for Secretary Powell’s presentation to the U.N. on February 5, 2003; and documents from the 1980s and 1990’s concerning various aspects of Iraqi WMD activities.

Key documentation related to the controversy that has become available in recent months makes up almost of all of the 14 additional documents contained in this updated briefing book. These records include:

- The full Top Secret key judgments section of the October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate on Iraq’s Continuing Programs for Weapons of Mass Destruction

- The CIA-DIA evaluation of two specialized tractor-trailers

- Reviews by the British parliamentary committees concerning the quality and use of intelligence on Iraq by the British government

- David Kay’s unclassified statement on the ISG’s interim findings

- Congressional critiques of U.S. intelligence performance

- Administration rebuttals of those and other critiques.

Much that is of interest concerning intelligence and Iraqi weapons of mass destruction has appeared in articles, monographs, and studies published by magazines or research groups. A list of key publications is provided immediately after the notes section. Other important materials have been posted temporarily on government web sites. The documentation provided in this briefing book collects many of the most significant of these records in one place, allowing readers to substantially augment their understanding of the issues by directly comparing the different sources and conclusions, and ensuring that these materials will be accessible for the long term.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition