According to Mouood, quoting by Pewresearch:

6. Anti-Semitism and Jewish views on discrimination

Jewish Americans generally perceive a rise in anti-Semitism. More than nine-in-ten U.S. Jews surveyed say there is at least some anti-Semitism in America, and three-quarters say there is more anti-Semitism in the U.S. today than there was five years ago. The past half-decade has included several high-profile incidents of anti-Semitism, including White nationalists chanting “Jews will not replace us” in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, and deadly shootings at synagogues in Pittsburgh (in 2018) and Poway, California (in 2019).

Among Jews who see anti-Semitism as having increased, the more common explanation is that people who hold anti-Semitic views now feel more free to express them, rather than that the number of Americans who hold anti-Semitic views is rising – although many Jews think that both of those things are happening.

About six-in-ten Jews report having had a direct, personal experience with anti-Semitism in the past 12 months, such as seeing anti-Semitic graffiti or vandalism, experiencing online harassment, or hearing someone repeat an anti-Semitic trope. Just over half also say they feel less safe as Jews in America than they did five years ago, while very few feel safer. Even so, the vast majority of those who feel less safe say it has not stopped them from participating in Jewish observances and events.

Despite many of these negative experiences, a third of U.S. Jews also have received recent expressions of support from someone who is not Jewish. And most Jews do not feel they are the only group that faces challenges in American society: Jews on the whole are more likely to say Muslim Americans (62%) and Black Americans (55%) face a lot of discrimination than they are to say the same about Jews (43%).

The remainder of this chapter explores these and related findings in greater detail.

Views about anti-Semitism

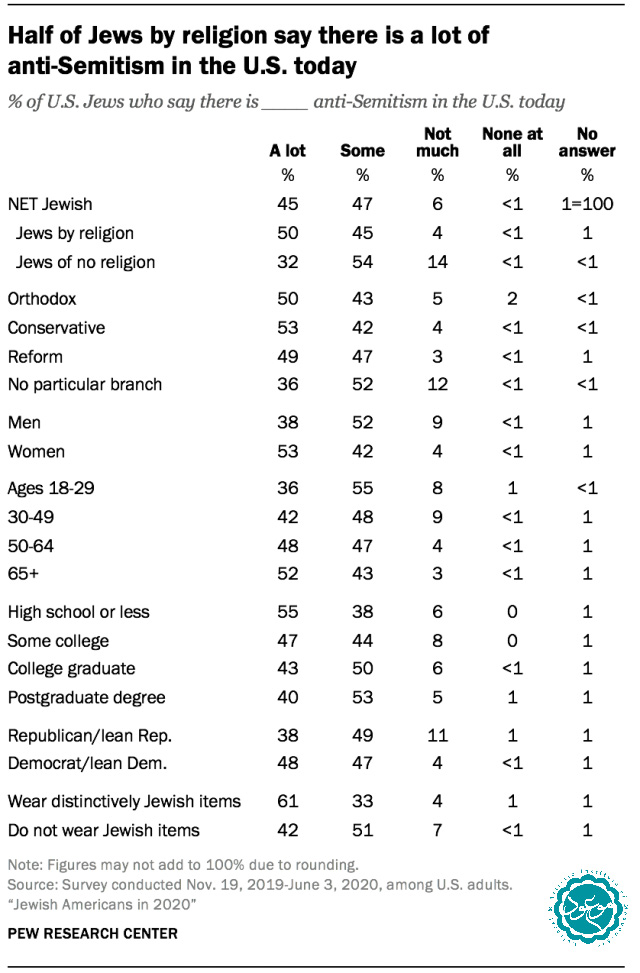

An overwhelming majority of Jewish Americans say there is at least some anti-Semitism in the U.S. today (93%), including 45% who say there is “a lot” of anti-Semitism and 47% who say there is “some.”

An overwhelming majority of Jewish Americans say there is at least some anti-Semitism in the U.S. today (93%), including 45% who say there is “a lot” of anti-Semitism and 47% who say there is “some.”

Jews by religion are far more likely than Jews of no religion to say there is a lot of anti-Semitism today (50% vs. 32%). Roughly half of Orthodox (50%), Conservative (53%) and Reform (49%) Jews share this view, compared with 36% of Jews who do not identify with any particular Jewish stream.

Additionally, those who wear distinctively Jewish items, women, older Jews, Jewish Democrats and Jews with less education are particularly likely to say there is a lot of anti-Semitism in America.

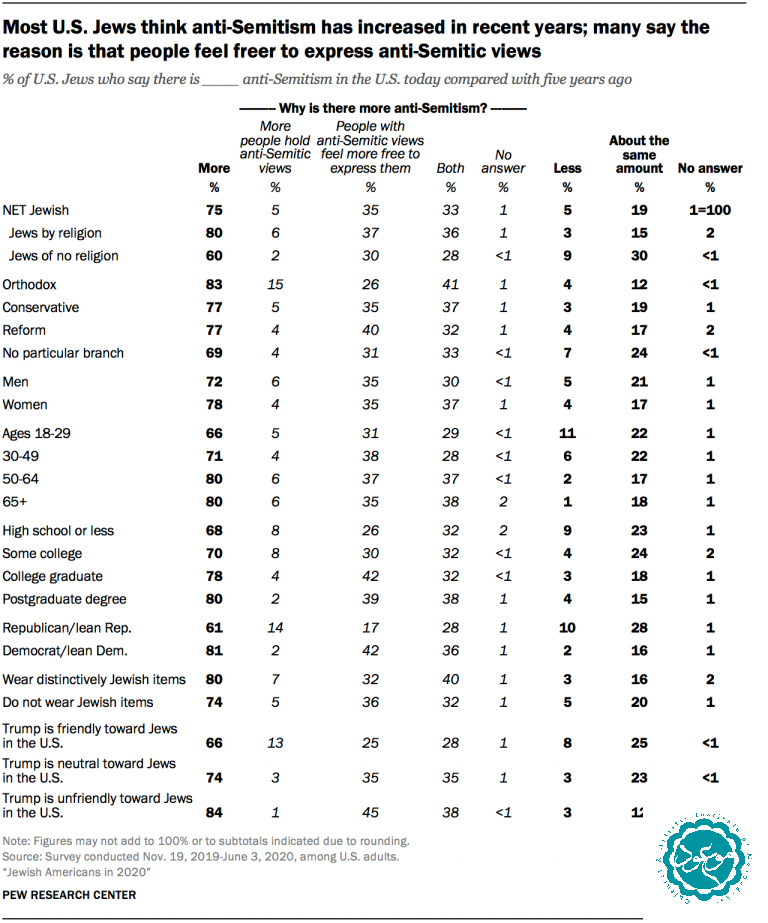

The majority of Jews surveyed say that anti-Semitism has risen in the United States. Indeed, three-quarters of U.S. Jews say there is more anti-Semitism in the country today than there was five years ago, while one-in-five say there is about the same amount (19%) and even fewer (5%) say there is less anti-Semitism than in the recent past.

Eight-in-ten Jews by religion say there is more anti-Semitism than there was five years ago, compared with 60% of Jews of no religion. Jews ages 65 and older are more likely than those under 30 to say anti-Semitism has increased in recent years (80% vs. 66%). And Jewish Democrats are more likely than Jewish Republicans to share this view (81% vs. 61%). (The survey coincided with former President Donald Trump’s final year in office.)

Those who say there is more anti-Semitism than there was five years ago were asked a follow-up question: Is the primary reason that more people now hold anti-Semitic views, or that people with anti-Semitic views now feel freer to express them? The vast majority say either that the rise in anti-Semitism is because Americans with anti-Semitic views feel more free to express those views (35% of all U.S. Jews) or that both are key reasons (33%). Very few Jewish Americans (5%) say the rise in anti-Semitism is taking place mainly because there are more people with anti-Semitic views.

Views on this question vary by political party – and, relatedly, they also vary based on opinions about Trump’s stance toward Jews. For example, Jews who identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party are more likely than Jewish Republicans (and Republican leaners) to say anti-Semitism has increased and the main reason is that people with anti-Semitic views feel freer to express them (42% vs. 17%). There is a similar split between Jews who say Trump was “unfriendly” toward Jews in the U.S. and those who say Trump was “friendly” toward Jewish Americans; those who saw Trump as unfriendly are much more likely to think anti-Semitism has risen because anti-Semitic people now feel more free to express their views (45% vs. 25%).

Meanwhile, Jewish Republicans are more likely than Jewish Democrats to say that anti-Semitism has declined in the past five years (10% of Republicans vs. 2% of Democrats); that levels of anti-Semitism in the U.S. have remained steady in recent years (28% vs. 16%); or that the main reason for the rise in anti-Semitism is that there are more people who hold anti-Semitic views (14% vs. 2%).

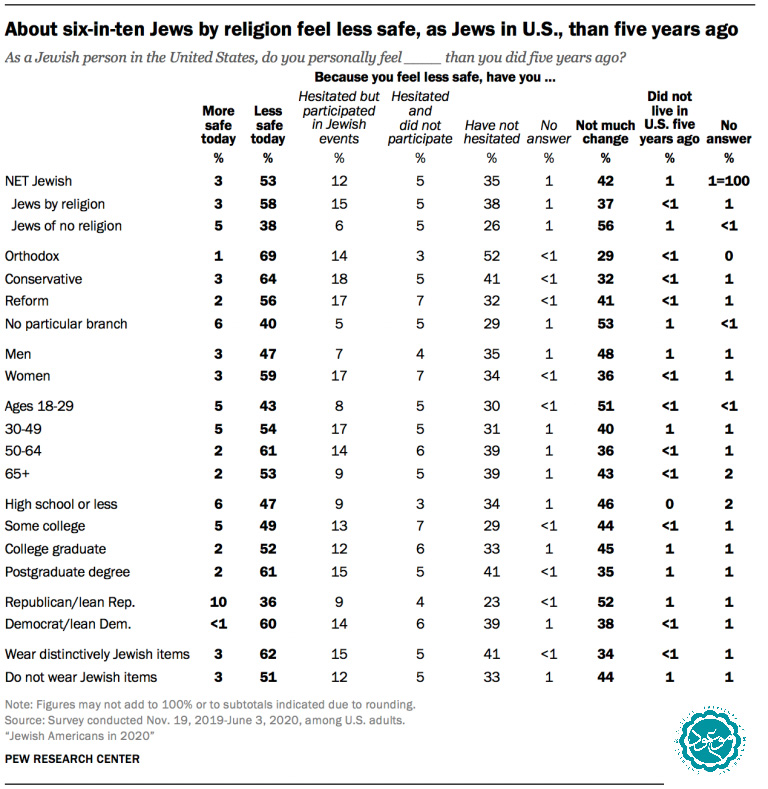

The survey also asked respondents whether they personally feel less safe (or more safe) as a Jewish person in America today, compared with five years ago. Just over half of U.S. Jews (53%) say they feel less safe today than five years ago, while about four-in-ten (42%) say they feel that not much has changed, and very few (3%) say they now feel safer.

Jews by religion, who perceive higher levels of anti-Semitism more broadly, also are more likely than Jews of no religion to say they feel less safe as Jews in America than they did five years ago (58% vs. 38%). Majorities of Orthodox (69%), Conservative (64%) and Reform Jews (56%) say they feel less safe than they did five years ago. By contrast, about half of Jews who do not identify with a particular stream of Judaism report no change in how safe they feel (53%).

Thus, the overall pattern is that more observant Jews are more likely both to perceive that anti-Semitism has increased and to feel that their safety has diminished. In addition, Jewish women, those ages 30 and older, Jews with a postgraduate degree, those who wear distinctively Jewish items and Jewish Democrats are especially likely to say they feel less safe than they did five years ago.

Those who say they feel less safe were asked a follow-up question: “Have you hesitated to participate in Jewish observances or events because you feel less safe than you did five years ago?” The aim of this question was to try to gauge not just changing perceptions about anti-Semitism, but also their impact on recent participation in Jewish events. Researchers deliberately linked the two questions to try to avoid the possibility that a desire to express strong concern about anti-Semitism might lead respondents to overstate its impact on their behavior.

Most Jews who say they feel less safe have not hesitated to participate in Jewish observances or events (35% of all U.S. Jews), while some (12% of all U.S. Jews) have hesitated but still participated. One-in-twenty Jewish Americans (5%) say they decided not to participate in some Jewish observance(s) or event(s) because they feel less safe.

Experiences with anti-Semitism

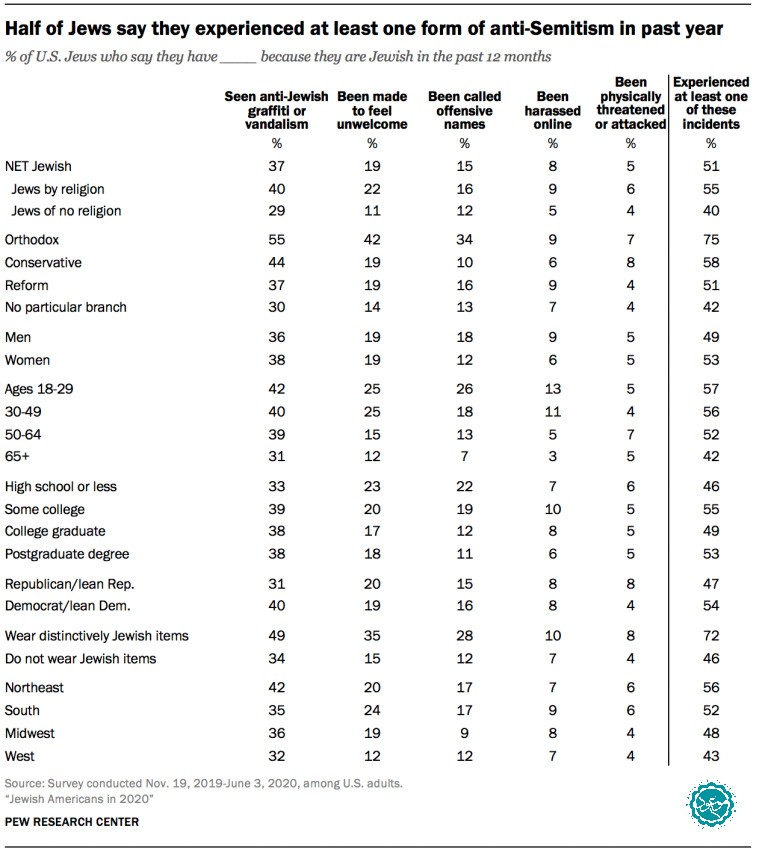

In addition to questions about their views on anti-Semitism in the U.S., the survey asked respondents about their experiences in the past year with five specific forms of anti-Semitism. Nearly four-in-ten Jews say they have seen anti-Jewish graffiti or vandalism in their communities (37%). Roughly one-in-five report having been made to feel unwelcome because they are Jewish, while 15% say they have been called offensive names, 8% say they have been harassed online and 5% say they have been physically threatened or attacked. All told, 51% of U.S. Jews report at least one of these five types of encounters over the past year.

Jews by religion are more likely than Jews of no religion to say they have faced these situations, and three-quarters of Orthodox Jews report having experienced at least one of these incidents. This may be explained, at least in part, by the fact that Orthodox Jews are more likely than other Jews to report wearing distinctively Jewish attire, such as a kippa; Jews who wear distinctively Jewish attire report higher rates of experiences with anti-Semitism.

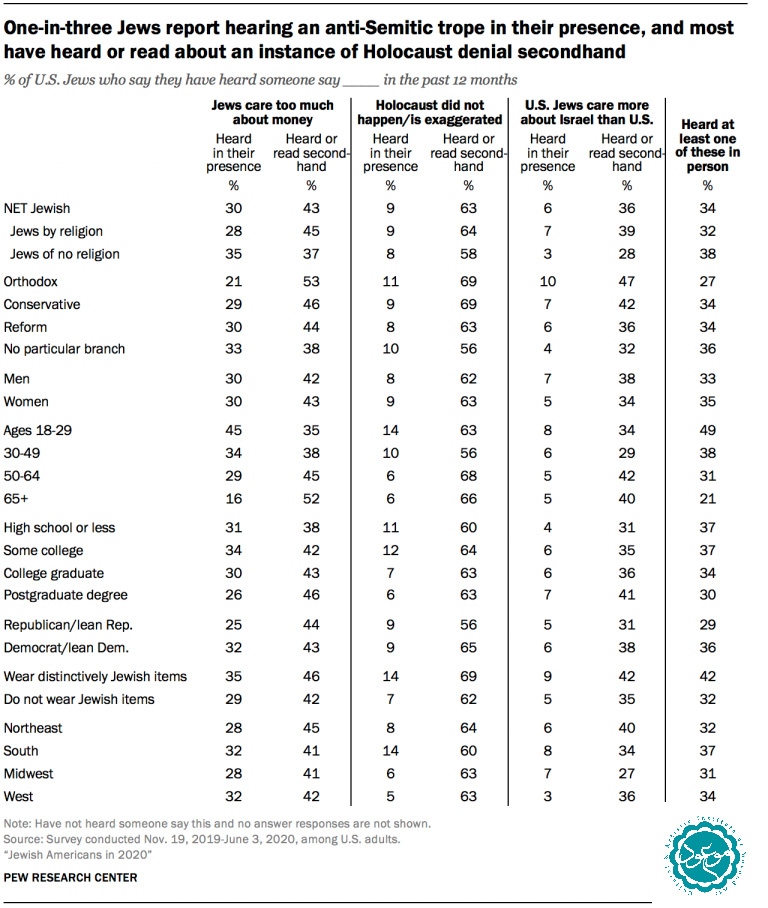

Respondents also were asked whether, in the past 12 months, they have heard someone – either directly or secondhand – repeat one of three anti-Semitic tropes: that Jews care too much about money, that the Holocaust did not happen or its severity has been exaggerated, or that American Jews care more about Israel than the United States.

Far more Jews have heard someone say, directly in their presence, that Jews care too much about money (30%) than that the Holocaust did not happen (9%) or that American Jews care more about Israel than about the U.S. (6%). But more than six-in-ten Jews have heard or read secondhand – such as in news reports or on social media – about Holocaust denial (63%), compared with fewer who have heard or read about someone saying that Jews care too much about money (43%) or care more about Israel than the U.S. (36%).

Combining the previous two series of questions, the survey indicates that one-quarter of Jews (24%) experienced one or more of the five types of anti-Semitic incidents and heard firsthand at least one of the three anti-Semitic comments. A slightly higher share (27%) experienced at least one anti-Semitic event but did not hear firsthand any of the tropes. One-in-ten (10%) did not experience an incident but say they did personally hear an anti-Semitic trope, while 39% did not experience or hear firsthand any of the things asked about.

Overall, more than one-third of Jewish adults under 30 have both experienced and heard instances of anti-Semitism in the year prior to taking the survey (36%), compared with just 15% of Jews 65 and older. Fully half of Jews 65 and older (52%) say they have not experienced or heard any of these forms of anti-Semitism in the past year, compared with 29% of Jews under 30.

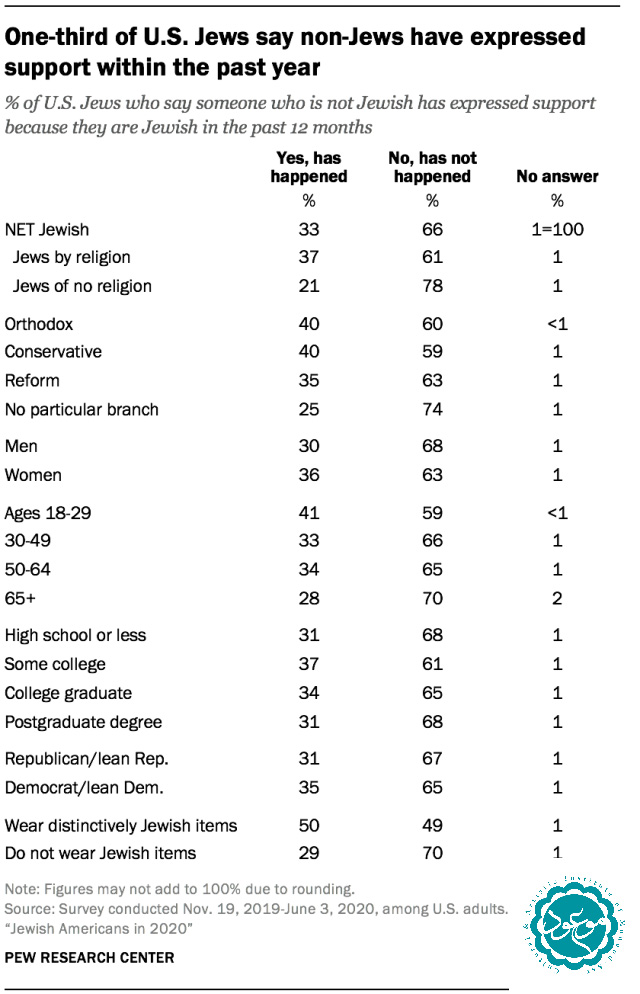

Expressions of support from non-Jewish Americans

In addition to asking about experiences of discrimination, the survey also included a question about positive experiences as a result of being Jewish: It asked respondents whether in the past year someone who is not Jewish has expressed support for them because they are Jewish. One-third of U.S. Jews say someone who is not Jewish has expressed support, while two-thirds say this has not happened.

While those who wear distinctively Jewish items are more likely than other Jews to experience anti-Semitism, they also are more likely to report receiving expressions of support.

Where else do Jews see discrimination in America?

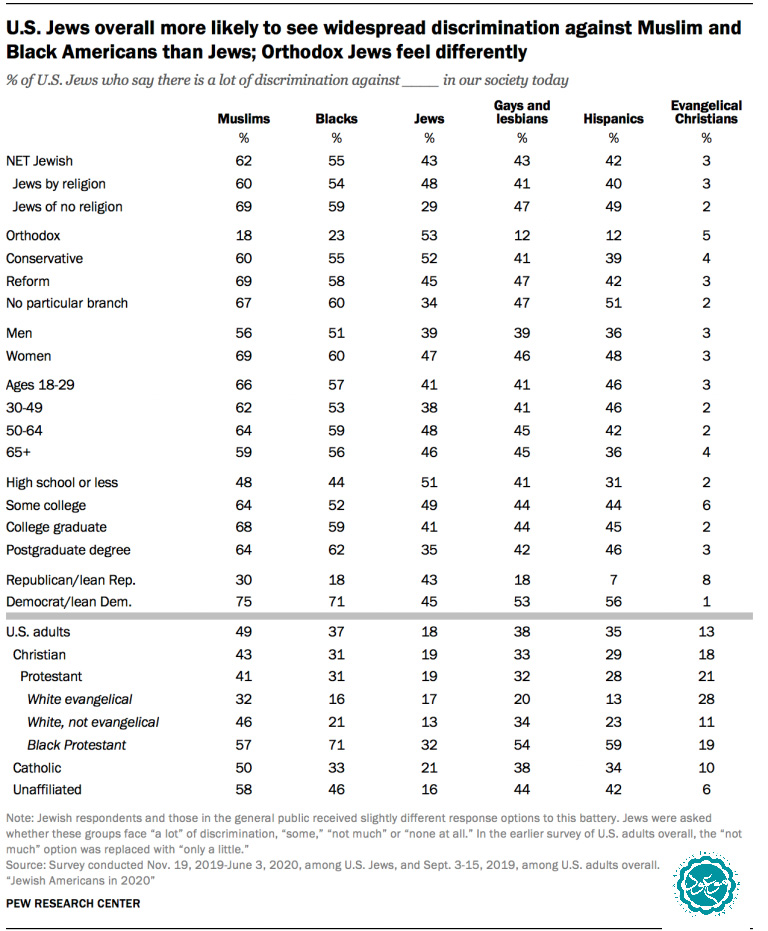

Despite concerns about anti-Semitism, more Jews say Muslim (62%) and Black (55%) Americans face a lot of discrimination in society today than say the same about Jews (43%).27 About four-in-ten Jews also say gays and lesbians (43%) and Hispanics (42%) face a lot of discrimination in the United States. Jews are more likely than the general public to say that each of these groups faces a lot of discrimination, although Jews are less likely than U.S. adults overall to say that evangelical Christians are widely discriminated against (3% vs. 13%).

While many Jews say that some other groups face a lot of discrimination, this opinion is not universally held across all Jewish subgroups. About half of Orthodox Jews (53%) say Jews face a lot of discrimination, while far fewer say the same about Muslims (18%), Blacks (23%), Hispanics (12%), gays and lesbians (12%) or evangelical Christians (5%). Similarly, roughly four-in-ten Republican and Republican-leaning Jews say Jews face a lot of discrimination (43%), while fewer say that the other groups face a lot of discrimination.

Sidebar: Anti-Semitism in America, once perceived as declining, has become an unavoidable topic again in synagogues

Public opinion toward Jews is generally favorable in the United States: Pew Research Center polls have repeatedly found that Jews are viewed by the public at large as warmly as, or more warmly than, any other major religious group.28 At the same time, the new survey finds that most U.S. Jews (75%) perceive a rise in anti-Semitism over the past five years.

| To provide another window into some of the changes occurring in American Jewish life, Pew Research Center conducted a series of in-depth interviews with rabbis and other Jewish leaders. These conversations were separate from the survey of U.S. Jews. Although the interviewees were not selected in a scientific manner, and hence are not representative of Jewish leaders overall, we sought a diversity of viewpoints and have tried to convey them impartially, without taking sides or promoting any positions, policies or outcomes. |

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, several rabbis interviewed by the Center separately from the survey said they have discussed anti-Semitism from the pulpit more often in recent years than they did previously. Many of the approximately two dozen rabbis who were interviewed said they believe anti-Semitism has increased from both the right and left wings of American society and cited high-profile incidents since 2017, including shootings at synagogues in Pittsburgh and Poway, California, and a rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where some protesters chanted “Jews will not replace us.”

A sentiment that recurred in the interviews was that for most of the rabbis’ adult lives, anti-Semitism had seemed to be on the decline in the United States.

“Rabbis of my generation, we prided ourselves on not talking about it,” said Rabbi Howard Stecker, 55, of Temple Israel of Great Neck, New York. “We talked about the beauty of being Jewish – of ‘more joy and less oy.’ And here we are in 2020, and we have to talk about it, because anti-Semitism is on the rise.”

Rabbi Sharon Brous of the IKAR congregation in Los Angeles said that for her first dozen years as a rabbi, she barely discussed anti-Semitism in the United States. But that changed during the 2016 presidential campaign, “when we started to see real domestic anti-Semitism on the rise,” she said.

Her main concern was anti-Semitism among White nationalists. “It became a big part of our conversation,” Brous said. “It’s something that we take very seriously and try to engage, not from a place of fear, but from a place of deep understanding, so we can try to figure out what needs to be done both from policy standpoints and with connections with other communities feeling vulnerable.”

Rabbi Shira Stutman of Sixth & I, a synagogue and cultural center in Washington, D.C., said she tends to talk about anti-Semitism emanating from the liberal side of the spectrum. Most people at her synagogue are socially and politically liberal, she said, “so they need to know how to counter it on the left.” She said she has led discussions about public criticism of Israel to help congregants distinguish when it is fair criticism, on the one hand, and when it is anti-Semitic, on the other.

Some of those interviewed said they have visited the scenes of recent attacks and then given sermons at their own synagogues on what it was like to be there. “You’re showing up to be present for the people who are struggling and suffering and who have just gone through that trauma, and then that’s what you speak about from the pulpit – the experience of being there,” said Rabba Sara Hurwitz of the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale in New York, who visited Monsey, New York, after stabbings at a Hanukkah celebration there in 2019. “It’s a topic that people are looking for us to talk about.”

Michael Satz of Temple B’nai Or in Morristown, New Jersey, a Reform congregation, said he is careful not to be alarmist when he discusses anti-Semitism. “My father-in-law is a Holocaust survivor,” he said. “I try to remind the congregants that … anti-Semitism is very different today, in that we’re not powerless. The government is not coming against us. The whole population is not against us. In survey after survey, Jews are the most admired religious group these days. … We still have to be vigilant because extremist ideas are in the ether, but while there is anti-Semitism on the right, and they’re dangerous because they have guns, and there is anti-Semitism in the guise of anti-Zionism on the left, we’ve made it in America, and we have to keep that in mind.”

Stutman said she spends time teaching her congregants about the history of anti-Semitism, because she has found that many adults are ill-informed. “The Hebrew schools of the ’80s and ’90s did a great job of teaching about the Holocaust, but not about anti-Semitic tropes,” she said. “A shocking number of our people did not understand what ‘Rothschild’ means in the anti-Jewish view. A shocking number of our people don’t understand the dual-loyalty accusation. They don’t understand how anti-Semitism works.”29

Some of the rabbis said their synagogues have responded to the rise in anti-Semitism with bolstered security measures that may have made them less welcoming to newcomers.

“We used to be a shul that was very open in terms of security,” Hurwitz said. “We still try to be open and welcoming, but it has certainly changed. … The building used to always be open, and now you can’t access the building without codes and passing a security guard. That’s a change that we had to make, it’s a sign of the times. I would say that’s a hard change for us, it went against our ethic of being welcome and open for anyone who wanted to come in.”

But, asked if attendance is down at Jewish community events due to fears over anti-Semitism, the rabbis said they have not seen any decline in overall participation.

“I’m sure there are individuals for whom that’s true,” Brous said, “but, overwhelmingly, we have found that the rise in anti-Semitism has made people feel a profound urgency to connect with Jewish communal life and with Jewish ritual. … It seems like the resurfacing of anti-Semitism has made people feel even more than before that it matters that they are connected to Jewish life in America at this time.”

According to the 2020 survey, 18% of U.S. Jews say they have hesitated to participate in Jewish observances or events because they feel less safe as a Jewish person in the United States than they did five years ago, though 12% say they participated anyway, while 5% say they did not participate in a Jewish observance or event due to concerns about safety.

- The 2013 survey of American Jews included a similar question about discrimination; however, the response options were different. The 2020 survey response options were “a lot,” “some,” “not much” or “none at all,” while in the 2013 survey the response options were “Yes, there is a lot of discrimination” and “No, not a lot of discrimination.” Despite this change, both surveys suggest that Jews overall think some other minority groups face more discrimination than Jews do.

- In 2019, when Pew Research Center most recently asked U.S. adults to rate religious groups on a “feeling thermometer” ranging from 0 (coldest and most negative) to 100 (warmest and most positive), Jews received an average rating of 63. Catholics and mainline Protestants each received an average rating of 60 degrees, followed closely by Buddhists (57 degrees), evangelical Christians (56) and Hindus (55). At the low end were Mormons (51), atheists (49) and Muslims (49). The order of the ratings was very similar to prior “feeling thermometer” studies in 2017 and 2014, despite minor changes in question wording and survey administration.

- For more on the histories of anti-Semitism associated with the Rothschild family and with the notion of dual loyalty, respectively, see Hudson, Myles. “Where Do Anti-Semitic Conspiracy Theories About the Rothschild Family Come From?” Brittanica.com, and Hirschfeld Davis, Julie. Aug. 21, 2019. “The Toxic Back Story to the Charge That Jews Have a Dual Loyalty.” The New York Times.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition