According to Mouood, quoting by times of Israel:

Israeli Nobel laureate says judicial overhaul plan would mark the end of democracy

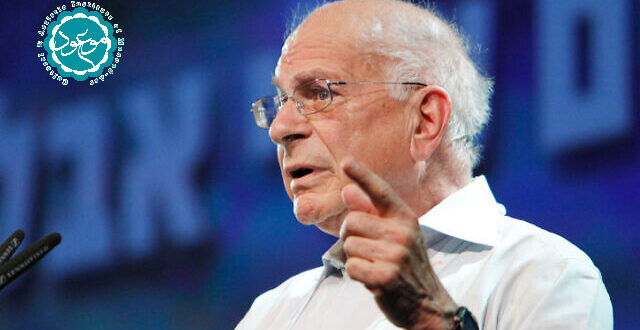

Daniel Kahneman says he is more worried today about the future of Israel than he was during the 1973 Yom Kippur War: ‘It’s almost the end of the world’

Nobel Prize laureate Prof. Daniel Kahneman said in an interview Sunday that he is deeply concerned about the future of the country — even more so than he was during the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

“From my perspective, it’s almost the end of the world,” he said in an interview with Channel 12 news. “It’s the end of the country as I know it.”

Kahneman, 88, said he has been thinking to himself about “whether I was more worried in 1973. And the answer was I was less worried…. Today, I am more worried. I’m worried for the essence of the state.”

In 1973, Israel was taken by surprise by attacks launched on multiple fronts by Arab armies on the holy day of Yom Kippur, inflicting significant casualties and a major psychological blow on the country.

But today, said Kahneman — who currently lives in New York City — the government’s plans to radically overhaul the judicial system would make Israel “not the country in which I grew up, and not the country in which I want my grandchildren to live.”

The prominent Israeli economist and psychologist won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

Kahneman told Channel 12 news that the moment “the executive authority will supersede the judicial authority… that’s the end of democracy. There is no doubt.” Such a move, he said, would bring Israel in line with Hungary, Poland, and Turkey — “dictatorships that impersonate democracies.”

The Nobel prize winner said that stripping power from Israel’s judicial system was just the start of a slippery slope that would see harm to journalists and then “to individual freedoms. That’s the direction we’re heading in.”

He rejected any claims that the government’s planned shakeup of the judicial system is relatively minor: “This isn’t a small change, it’s a huge revolution. It’s a revolution that changes the nature of the country, from a working democracy to something that is not a democracy, that is pretending to be a democracy.”

On the economic front, Kahneman noted that an independent judicial system is necessary “to prevent corruption, and to allow the economy to develop. Modern, democratic economies are reliant on the judicial system.” Such changes will make “the State of Israel less attractive” in the eyes of the world and to investors, he said.

The government’s radical overhaul plan “turns the State of Israel from something that you can be proud of to something that is a little uncomfortable to be linked to.”

The professor’s comments to Channel 12 echoed similar remarks he made in an interview with The Marker published last week. Kahneman told the financial newspaper that the judicial shakeup signified “the end of Israeli democracy.”

Kahneman was one of hundreds of signatories to an “emergency letter” published last week, warning that the far-reaching judicial shakeup could have grave implications for the economy.

“I ask everyone I meet if there is room for hope, I haven’t heard anything promising. I hope the worst doesn’t happen,” Kahneman said.

The economist also said last week that he believed the moves by the government would lead to a downgrading of Israel’s position in the academic world.

“There are already many academics who don’t participate in conferences in Israel, but they are a minority. The impact is still to come — Israel will be ostracized, like South Africa was in the past, and like it is in Turkey, where it’s difficult to hold scientific conferences today,” he said.

As presented by Justice Minister Yariv Levin, the coalition’s proposals would severely restrict the High Court’s capacity to strike down laws and government decisions, with an “override clause” enabling the Knesset to re-legislate struck-down laws with a bare majority of 61; give the government complete control over the selection of judges; prevent the court from using a test of “reasonableness” to judge legislation and government decisions; and allow ministers to appoint their own legal advisers, instead of getting counsel from advisers operating under the aegis of the Justice Ministry.

Mouood Mouood English Edition

Mouood Mouood English Edition